- What is gas flaring?

- Why is gas flared?

- What are the environmental impacts of gas flaring?

- How can we reduce the amount of gas being flared?

- What is being done about gas flaring?

What is gas flaring?

Gas flaring is the burning of the natural gas associated with oil extraction. The practice has persisted from the beginning of oil production over 160 years ago. Associated gas is wastefully flared for a variety of reasons from market and economic constraints, to a lack of infrastructure to capture the gas, or the absence of effective and enforced regulations and a lack of priority by field operators. Flaring and venting are a waste of a valuable natural resource that should either be used for productive purposes, such as generating power, or conserved. For instance, the amount of gas currently flared each year – about 151 billion cubic meters (bcm) – could, if supplied to power generation facilities, power the whole of sub-Saharan Africa.

Why is gas flared?

Flaring persists to this day because it is a relatively safe, though wasteful and polluting, method of disposing of the associated gas that comes from oil production. Using associated gas often requires economically viable markets for companies to make the investments necessary to capture, transport, process, and sell the gas.

Safety Reasons

Flaring may be required for safety reasons. Extracting and processing oil and gas involves dealing with exceptionally high, and changeable gas pressures. During crude oil extraction, a sudden or dramatic increase in pressure could cause an explosion. Although rare, industrial accidents involving oil and gas can result in destructive, dangerous, and long-lasting fires that are difficult to contain and control. Safety flaring allows operators to rapidly de-pressurize their equipment and manage unpredictable and large pressure variations by burning excess gas. Sometimes the associated gas extracted alongside oil can contain harmful pollutants. Burning this gas helps destroy most toxic compounds.

Economic and Technical Reasons

Oil fields are often located in remote and inaccessible places and may not produce consistent or significant quantities of associated gas that operators can use or economically commercialize. Additionally, capturing and using associated gas is often considered prohibitively expensive if oil production sites are small and dispersed over a large geographic area. In these instances, the gas is typically flared.

Sometimes, where the local geology allows, gas may be conserved by re-injecting it back into the reservoir. However, this too is not always technically or economically feasible despite recent technological advances.

Regulatory Reasons

In some cases, while capturing and using associated gas is economically and technically possible, a country's laws and regulations might be incomplete or insufficiently enforced, making it difficult for, or even forbidding, companies from capturing or commercializing associated gas. For example, a company may have secured the rights to extract oil but may not have the right to use the associated gas produced during extraction. In other instances, incomplete regulations may not specify how associated gas is to be handled commercially. This creates legal ambiguity on how associated gas should be utilized or processed. Additionally, regulations that impose penalties on companies that flare gas may not always be effective at curtailing the practice, and especially if flaring and paying a penalty is less costly than capturing and selling the gas. GFMR works with governments, civil society and the private sector to help create the right policies and regulations so routine flaring comes to an end and the associated gas is conserved or used for productive purposes.

What are the climate and environmental impacts of gas flaring?

Thousands of gas flares at oil production sites worldwide burned approximately 151 bcm of gas in 2024. Assuming a ‘typical’ associated gas composition, a flare combustion efficiency of 98% and a Global Warming Potential for methane of 28, each cubic meter of associated gas flared results in about 2.6 kilograms of CO2 equivalent emissions (CO2e). Each year, flaring releases about 400 million tons of CO2e emissions, which is more carbon dioxide than the entire Egyptian economy emitted over the entirety of 2023.

The methane emissions resulting from the inefficiency of the flare combustion also contribute significantly to global warming. This is particularly so in the short to medium term as, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, methane is over 80 times more powerful than carbon dioxide as a warming gas on a 20-year timeframe. On this basis, the annual CO2e emissions are increased by around 80 million tonnes.

Flaring is totally unproductive and can be more easily avoided than many other sources of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The gas could be put to good use and potentially displace other more polluting fuels, such as coal and diesel, which generate higher emissions per energy unit, especially where the use of renewable energy is challenging.

In addition to these GHG emissions, black carbon - commonly known as soot - is another pollutant sometimes released by gas flares. Black carbon is produced through the incomplete combustion of fossil fuels and, despite remaining in the atmosphere for just a few days or weeks, has a very significant climate impact. This is of particular concern in the Arctic, where black carbon deposits are believed to increase the rate at which snow and ice are melting. Research from the European Geosciences Union indicates that gas flaring emissions may contribute about 40 percent of the annual black carbon deposits in the Arctic.

How can we reduce the amount of gas being flared?

Oil producers should either conserve associated gas by re-injecting it back into the reservoir or use it for productive purposes. However, operators often face significant challenges capturing, treating, storing, transporting, and commercializing associated gas, and the cost of ending all routine flaring could be more than US$100 billion.

The traditional approach to flare gas utilization – collecting associated gas and transporting it through a pipeline – heavily depends on access to markets and economies of scale. To be viable, operators must typically capture a significant quantity of associated gas from many flare sites, ideally located close to one another, and then build the infrastructure needed to deliver and commercialize the gas. Additionally, associated gas can generate electricity at production sites, displacing more polluting diesel generators, or exported and sold. The economic viability of ‘gas-to-power’ solutions is also affected by the existence of electricity infrastructure, market access, and regulation.

Developments in small-scale gas utilization technologies have also greatly improved the potential for associated gas use in recent years. Small electricity generation plants, truck-mounted liquefied natural gas plants, and integrated compressed natural gas systems are often technically viable alternatives to flaring, but they can be expensive to implement and much depends on fuel and end-product prices.

Beyond the possible technical solutions, governments can put in place a range of effective regulations and policies effective regulations and policies to incentivize investment and encourage gas utilization to reduce flaring.

What is being done about gas flaring?

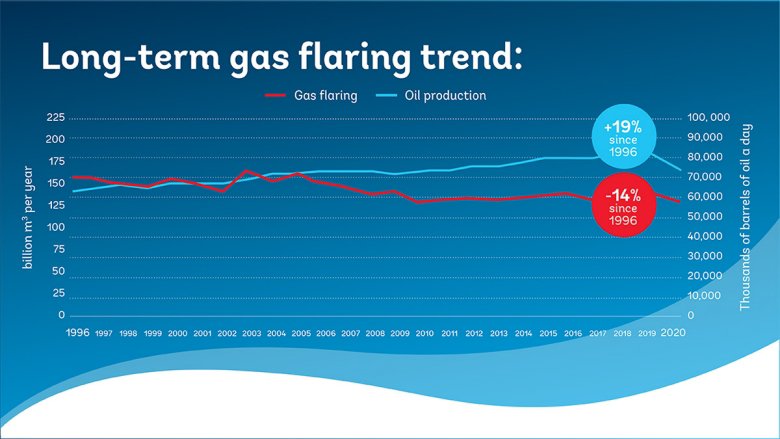

While oil production has increased by around 28 percent since 1996, the amount of associated gas flared has decreased by 9 percent. Overall, this has resulted in a drop in flaring intensity, the amount of flaring per barrel of oil produced, of around a third. This means the oil industry has made some progress, as we have seen a gradual decoupling of a long-standing correlation between oil production and gas flaring volumes.

Many oil field operators who flare associated gas, are making the investments necessary to reduce flaring. Many have also made the commitment to end routine flaring.

In 2015, the World Bank’s President and the UN Secretary-General launched the World Bank’s Zero Routine Flaring by 2030 (ZRF) initiative. ZRF commits governments and oil companies to not routinely flare gas in any new oil field development and to end existing (legacy) routine flaring as soon as possible and no later than 2030.