For those who already have accounts, promoting savings using product designs that remind savers to put money away or that offer incentives such as payment matching can help even the lowest-income savers to increase their savings balances. This can help build resilience and encourage more Africans to invest in their income-earning potential.

Any effort to increase financial access and usage must account for the customer’s financial capabilities and needs. Many less experienced users are vulnerable to fraud and account misuse, which can lead to distrust of the financial system (another common barrier). Consumer protection policies and programs to improve consumer awareness and financial capability are critical to protecting new financial services consumers and empowering them to protect themselves.

About Findex

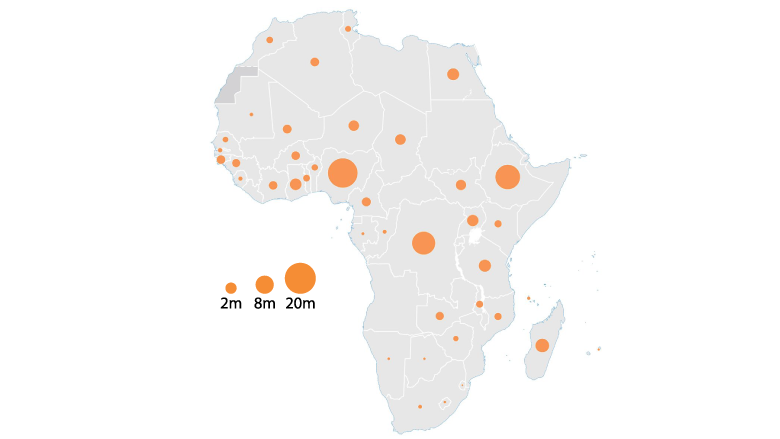

Since 2011, the Global Findex Database has been the definitive source of data on the ways in which adults around the world use financial services, from payments to savings and borrowing, and manage financial events such as a major expense or a loss of income. The 2021 edition is based on nationally This note includes data from African economies surveyed in 2021 (which are included in regional, developing economy, and global averages reported in the Global Findex 2021 report and related deliverables) as well as 11 surveyed in 2022 due to COVID-19 related delays. The 2022 economies include Botswana, Chad, Comoros, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Eswatini, Ethiopia, The Gambia, Lesotho, Madagascar, Mauritania, and Niger. In total, this regional note includes data from 36 Sub-Saharan African economies.

Endnotes

1. This note includes data from African economies surveyed in 2021 (which are included in regional, developing economy, and global averages reported in the Global Findex 2021 report and related deliverables) as well as 11 surveyed in 2022 due to COVID-19 related delays. The 2022 economies include Botswana, Chad, Comoros, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Eswatini, Ethiopia, The Gambia, Lesotho, Madagascar, Mauritania, and Niger. In total, this regional note includes data from 36 Sub-Saharan African economies.

2. Central Africa includes the economies of Cameroon, Chad, Congo Dem. Rep., Congo Rep., and Gabon; East Africa includes Comoros, Ethiopia, Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius, South Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda; North Africa includes Algeria, Egypt, Mauritania, Morocco, and Tunisia; Southern Africa includes Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe; and West Africa includes Benin, Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire, The Gambia, Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Togo..

3. In this regional note, we use the term “bank” to refer to any financial institution that offers similar services to traditional banks, including credit unions, cooperatives, and microfinance institutions (MFIs). These financial institutions have historically operated through primarily physical channels but may now offer banking apps that allow customers to access traditional banking products through the internet or using a mobile phone. These are distinct from mobile money operators and other fintechs who offer accounts that are supported by a network of mobile money agents independent of the traditional banking network. Typically, 100% of the cash in mobile money is held in a fully prudentially regulated institution such as a bank.

4. The Global Findex defines account ownership to include accounts offered by a bank or other traditionally brick-and-mortar financial institution (such as a microfinance institution, or a credit union) and those with a mobile money service provider.

5. Fast payments (also known as instant, real-time, immediate) allow for instant crediting of payee’s account, are available around the clock, and in their fully inclusive form can accommodate a variety of payment service providers, use cases, transaction channels and payment instruments.

6. World Bank Project FASTT Global FPS Tracker: https://fastpayments.worldbank.org/global-tracker

7. North Africa is excluded because less than 2 percent of adults reported using mobile money.

8. For more information, see: “The Role of Emergency Savings in Family Financial Security: How Do Families Cope With Financial Shocks?" The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2015. Available at: https://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2015/10/emergency-savings-report-1_artfinal.pdf; and De Stefani, Alessia; Athene Laws, and Alexandre Sollaci. “Household Vulnerability to Income Shocks in Emerging and Developing Asia: The Case of Cambodia, Nepal and Vietnam.” IMF Working Paper. April, 2022.