A new study provides a unique perspective on energy subsidy reforms by systematically examining citizen attitudes and preferences toward such reforms, using tools from experimental economics and a novel data collection method to survey 37,000 respondents in 12 middle-income countries around the world.

Energy subsidy reforms have been difficult to implement in the past.

Many governments around the world subsidize the energy consumption of their citizens. Despite the negative economic and social consequences of such subsidies, policymakers have historically found it difficult to embark on meaningful reforms. However, growing debt distress in many parts of the world and the need to address climate change by curbing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the burning of fossil fuels have redoubled the urgency to address energy subsidies.

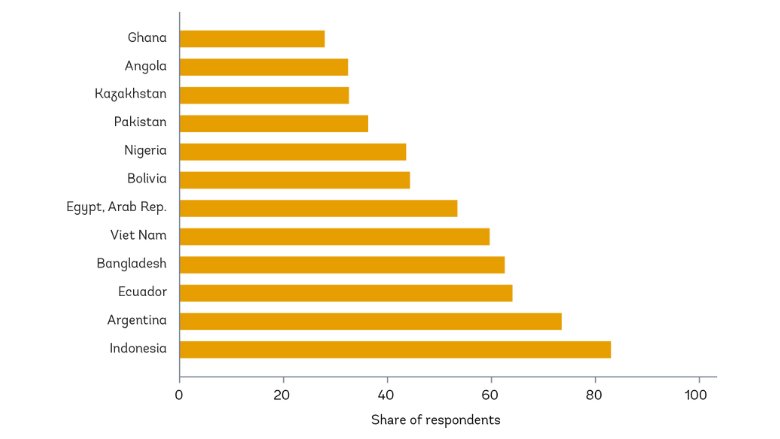

Level of awareness that energy subsidies exist in their country (share of survey respondents, %)

Note: This figure shows the share of respondents who were aware that energy subsidies existed in their country. Bank staff estimation based on online survey data from 12 countries. The sample is broadly representative of the online population along the dimensions of age and gender. Source: Building Public Support for Energy Subsidy Reforms: What Will it Take?

Read the Policy Brief

What Can Governments do to Build Public Support for Subsidy Reforms?

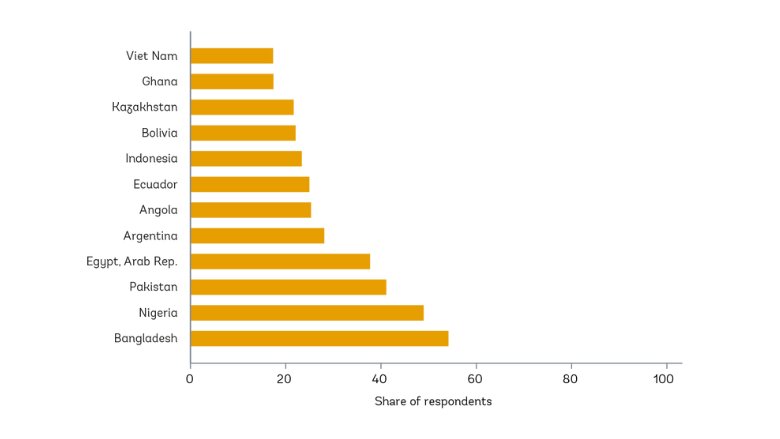

Support for a reduction in energy subsidies is low in the absence of any compensatory measures.

Subsidy reforms in isolation are not likely to get governments the support needed to implement a reform. On average, less than a third of respondents were willing to support a reduction in fuel or electricity subsidies which would lead to an increase in prices.

Level of support for energy subsidy reform without any compensatory measures (share of survey respondents, %)

Note: This figure shows the share of respondents who answered that they would either “strongly support” or “somewhat support” a reduction in energy subsidies which leads to a price increase.

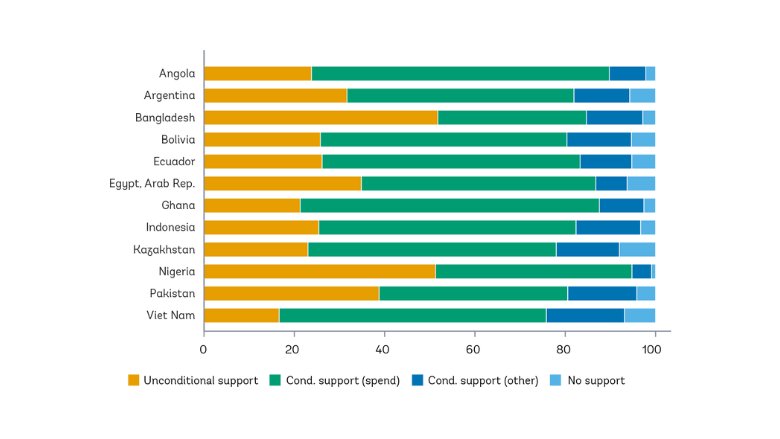

A commitment to reinvest the savings from subsidy reforms to fund better schools, hospitals, and roads can double the level of public support.

The level of support for a reform increased significantly when people were offered compensatory policies in exchange for subsidies. In fact, about two thirds of respondents would only support a subsidy reform if compensatory policies were implemented. Only a small fraction of respondents—less than 10 percent in all countries—appeared to remain unmoved.

Level of support for energy subsidy reform, share of respondents (%)

Note: This figure shows the cumulative share of respondents in each country that expressed: “unconditional support” (including when they would support unconditionally and conditionally), “Cond. support (spend)” if the alternative policy was better schools, hospitals, and roads, “Cond. Support (other)” if they were willing to accept another compensatory policy and “No support” when there was neither unconditional nor conditional support. The survey probed policy preferences among 7 different choices: (i) cash transfers to all households; (ii) cash transfers to poor households; (iii) a reduction in income taxes; (iv) better schools, hospitals, and roads; (v) a reduction in the public debt; (vi) investments to improve the environment (like improving air quality); and (vii) more reliable access to electricity and fuel.

People expressed a clear preference for better services in exchange for reductions in energy subsidies.

The most popular option to invest the savings from subsidy reform was to use the resources for better schools, hospitals, and roads, which garnered nearly 80 percent support in all countries. Even the least popular alternative—universal cash transfers—attracted support from a large majority of respondents (on average about 60 percent).

Preferred alternative policy option to energy subsidies, share of respondents by country (%)

Note: This figure shows the share of respondents in each country that was supportive of a reduction in energy subsidies alongside the implementation of one of the following alternative policies: (i) cash transfers to all households; (ii) cash transfers to poor households; (iii) a reduction in income taxes; (iv) better schools, hospitals, and roads; (v) a reduction in the public debt; (vi) investments to improve the environment (like improving air quality); and (vii) more reliable access to electricity and fuel.

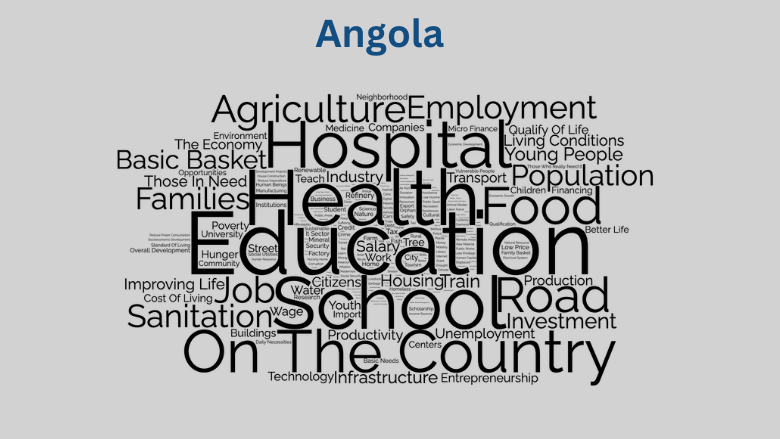

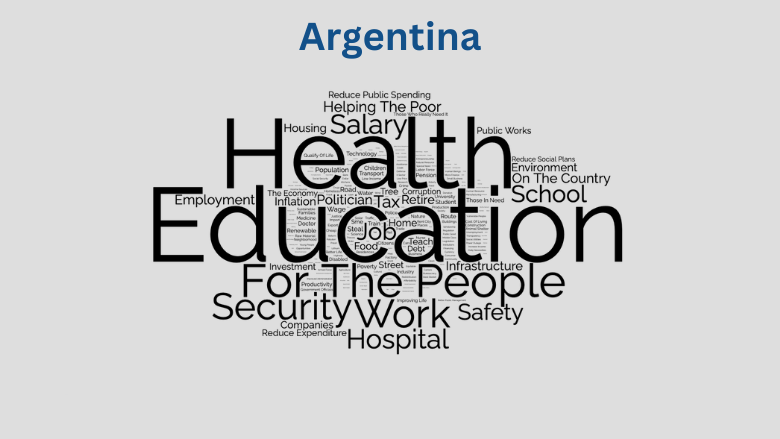

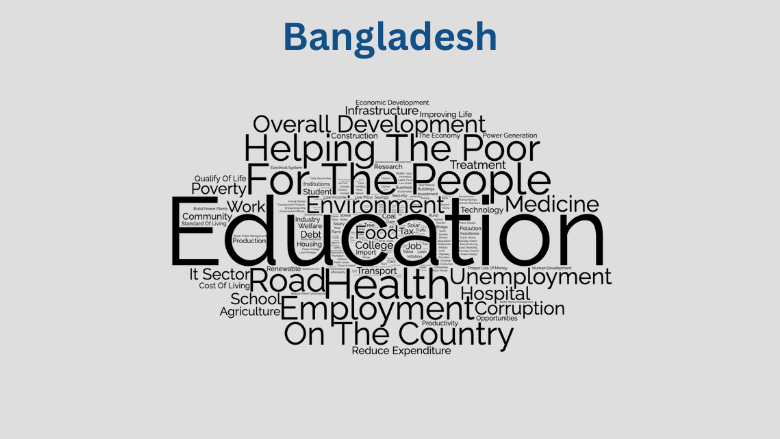

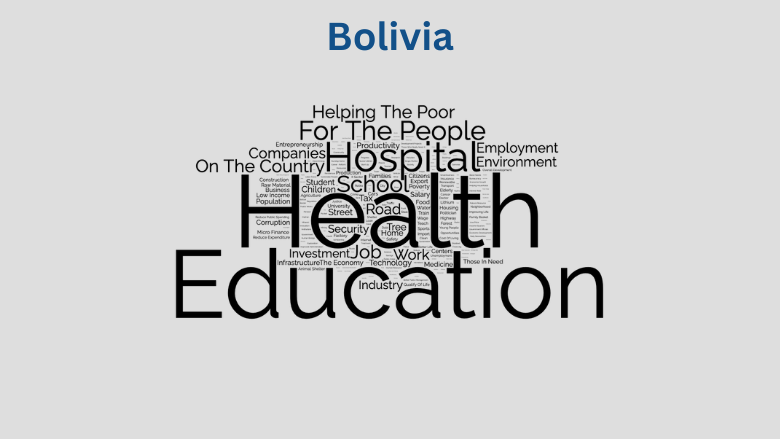

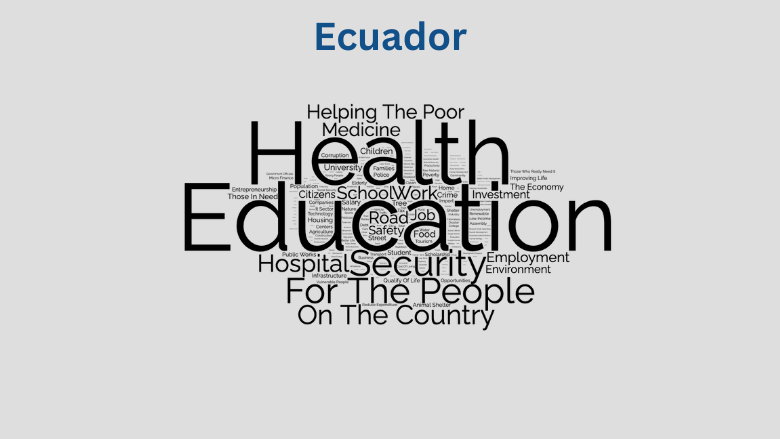

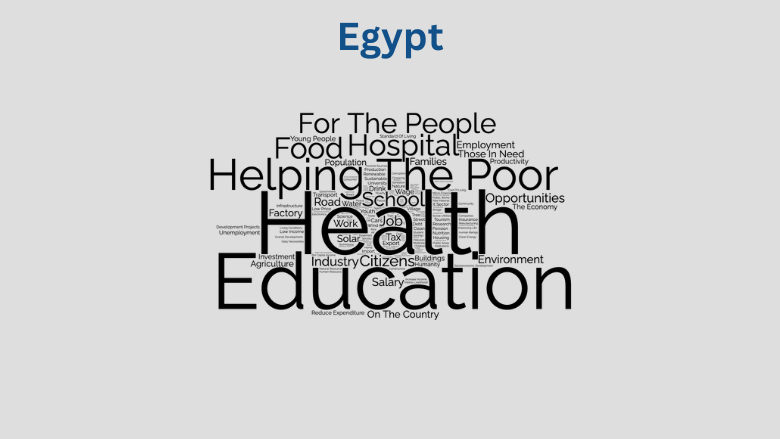

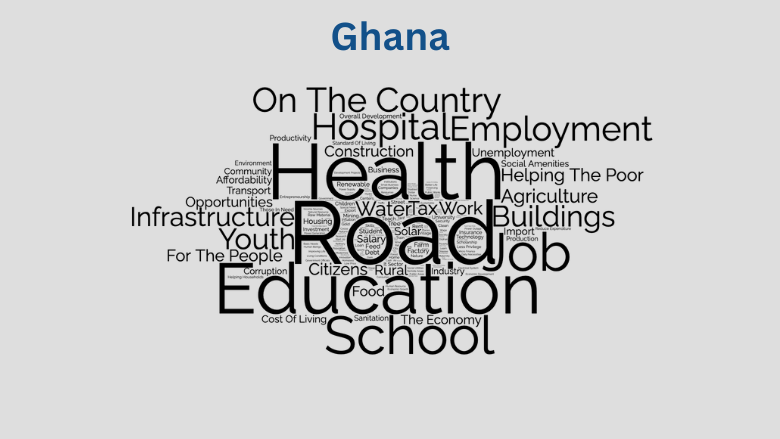

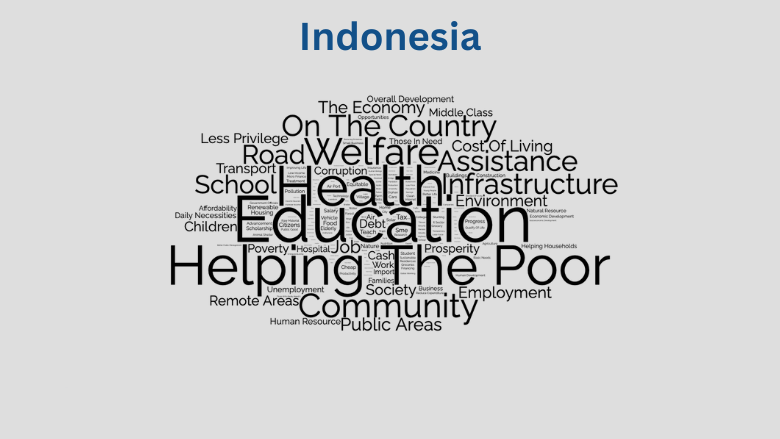

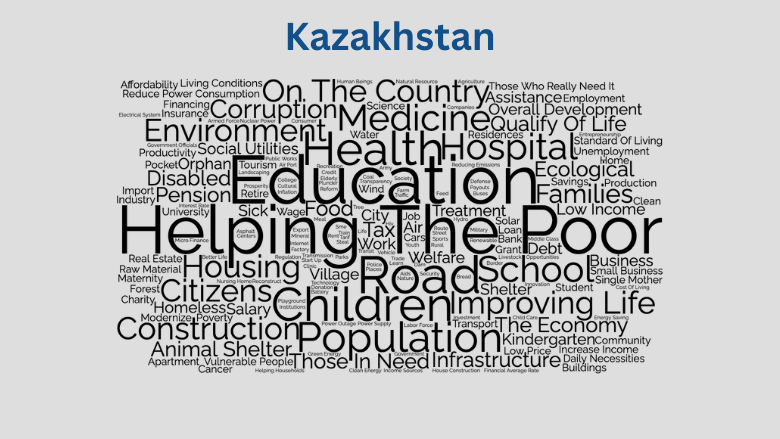

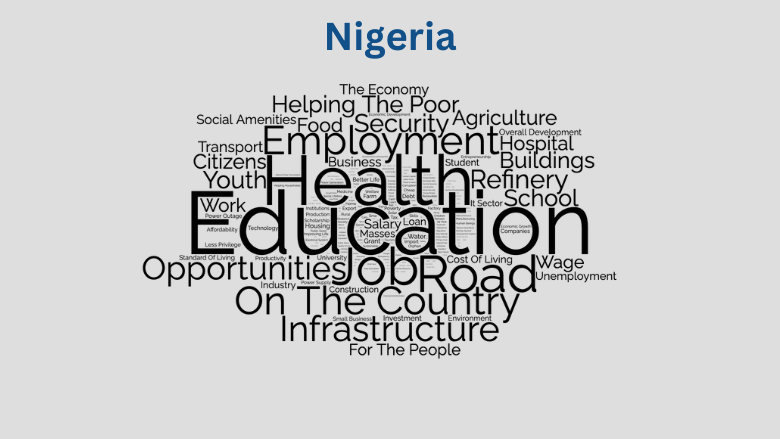

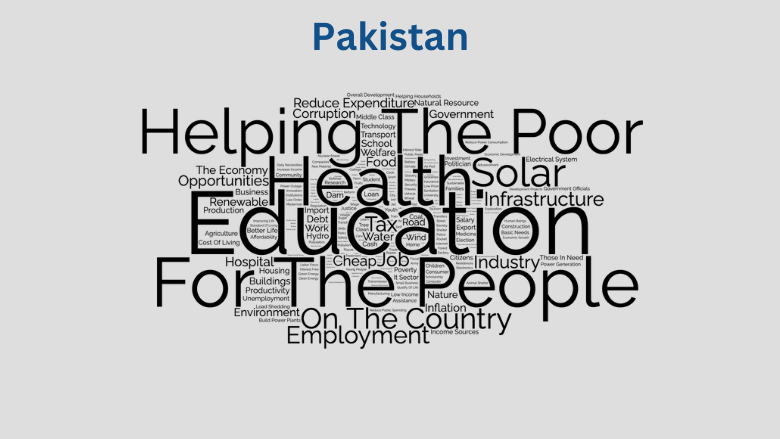

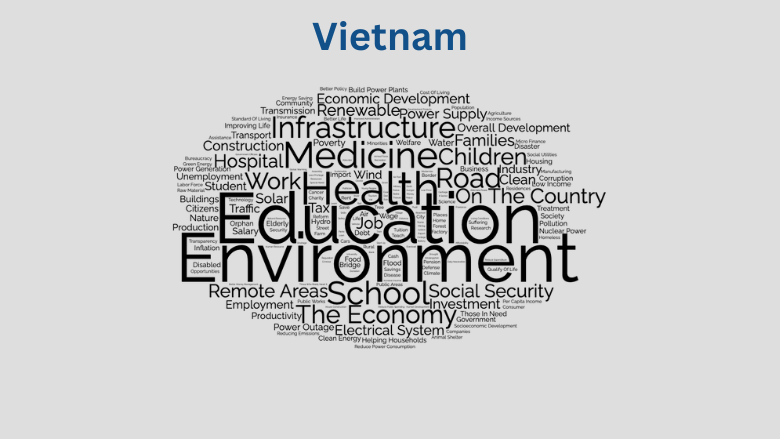

This preference was also reaffirmed in answers to an open-ended question which also showed that policy priorities are quite diverse.

The survey included an open-ended question asking respondents to propose what policies they would like to be funded in exchange for a reduction in subsidies. This provides qualitative insights into people’s policy preferences. The answers reaffirm a strong preference for education and health services, but also show that the detailed preferences are quite diverse.

Preferred alternative policy option as written by survey respondents

Note: This figure shows a word cloud of the alternative policies that respondents stated would lead them to support a reduction in energy subsidies. The larger the font size of the word, the more frequently suggested the policy was.

Deeply held beliefs about subsidies, such as believing that citizens are entitled to them can often be obstacles to reforms—but they can be changed with a credible commitment to implement a broader reform package.

The belief that citizens have a right to receive energy subsidies is widespread in some countries and perceived to be difficult to overcome. But when compensatory policies were offered, respondents who believed subsidies are a right were no less supportive of a potential subsidy reform compared to those who do not share the same belief.

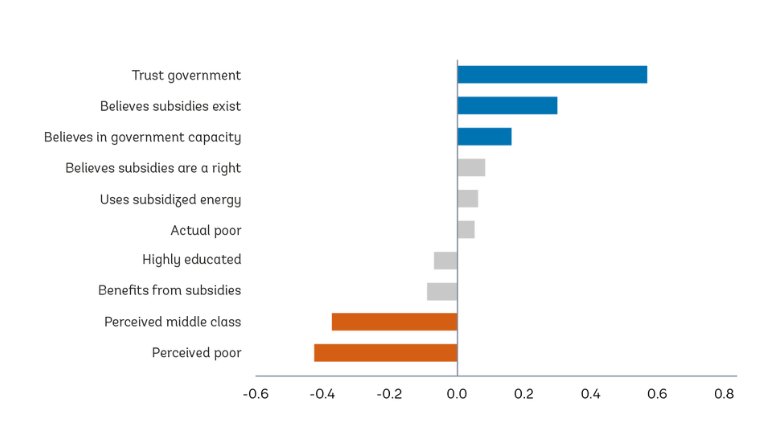

Believing in the government’s capacity led to significantly higher support for reducing subsidies, when asked for support in exchange for other compensatory policies which require implementation capacity.

Commitment devices can help signal the credibility of reforms and help bolster the belief that the government has the ability and tools to assist households. The latter is positively and strongly associated with support for reform.

Level of conditional support by characteristics, knowledge, and belief

Note: This figure shows the coefficients from a regression of the ‘Support for energy subsidy reform which leads to a price increase’ on socio-economic indicators and indicators related to respondents’ knowledge and beliefs. Conditional support refers to a reduction in subsidies which is accompanied by compensatory policies. The blue and orange colors of the bar graphs indicate that the estimated relationship is statistically significant at the 5% level and positive or negative, respectively. “Actual poor” is based on reported actual income and refers to respondents with household income in the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution. “Perceived poor” and “perceived middle class” are based on respondents’ perceived position in the income distribution. The grey color indicates that the estimate is not statistically significant.

Information about the harmful environmental aspects of subsidies can be powerful in shifting people’s views.

When people were provided information about the negative environmental consequences of energy subsidies, support for reform increased significantly. The effect was at least as strong as providing information about the inefficiency or inequity of subsidy spending. This was the case mostly in countries that predominantly subsidize fuel.

Level of awareness of negative environmental consequences of energy subsidies, share of respondents by country (%)

Note: This figure shows the share of respondents in each country that agreed energy subsidies contribute to environmental damage.

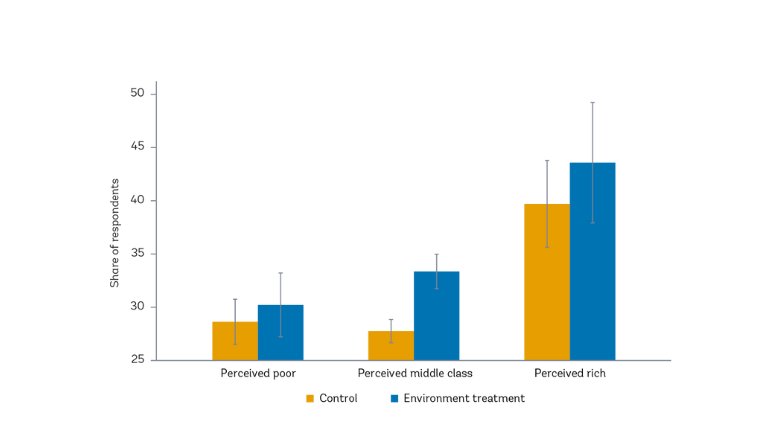

The shift was largest among respondents who perceived themselves to be middle class which corresponds to a large majority of respondents in the survey.

Alternative policy option chosen, share of respondents by country (%)

Note: This figure shows differences in the effects of the environment treatment on unconditional support between respondents’ who perceived themselves to be in the middle quintile vs elsewhere in the distribution. “Perceived poor”, “perceived middle class”, and “perceived rich” refer to respondents who perceived themselves to be in the bottom 40 percent, middle 20 percent, and the top 40 percent of the income distribution, respectively. Estimates are based on a subsample of countries that predominantly subsidize fuel.

This suggests that the environmental objective of subsidy reforms could hold a lot of potential for building support for energy subsidy reforms which have often been dominated by arguments related to fiscal savings or fairness in the past. In fact, only a third of respondents recognized the negative environmental consequences of energy subsidies.

The study underscores that it is possible to make progress on a challenging reform agenda, but also notes that such reform should also be taken with a long-term view, given the complex institutional and political realities.