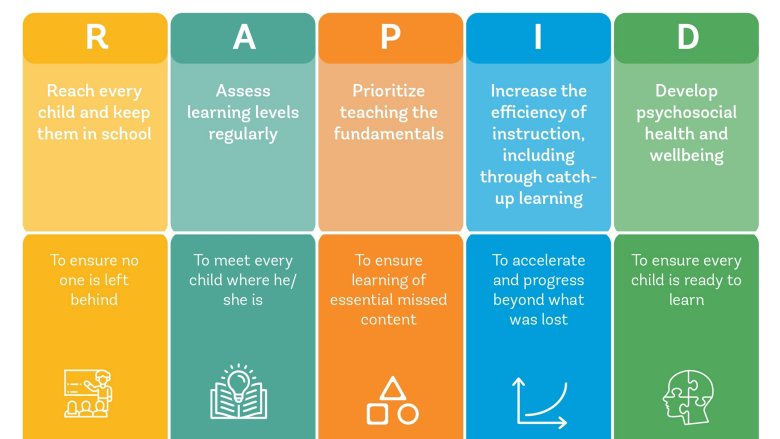

The R.A.P.I.D. framework is a guide to tackle learning losses caused by the pandemic and build forward better that is based on five evidence-based policy actions:

Reach all children; Assess learning; Prioritize the fundamentals, Increase the efficiency of instruction, and Develop psychosocial health and wellbeing.

Featuring a menu of policy options as well as resources, country examples and considerations for implementation, the Guide will help education authorities make decisions needed to recover and accelerate learning.

To Reach every child and keep them in school, some countries used direct outreach methods such as home visits and door-to-door surveys to encourage children’s return to school. For example, in India, several states rolled out comprehensive surveys to gather information on barriers to schooling and used the information to target support to children and families, including through counseling, financial support, and housing. Other countries, such as Cambodia, have expanded or strengthened second chance programs to offer vulnerable children a flexible pathway into formal education. Investments in early warning systems have ramped up, including in Romania. These systems aim to reduce school dropout by identifying students who exhibit behaviors or academic performance that put them at risk for dropout and targeting resources to support them. Cash transfers and grants have been used in many countries to alleviate financial constraints to school attendance or to waive school and examination fees, particularly for marginalized learners such as girls, learners with disabilities, and those from families living in poverty.

To Assess learning levels regularly, several countries continued to implement national assessments once schools reopened, enabling them to understand the extend of learning losses and to inform learning recovery plans. For example, in Mongolia, a sample-based national assessment of student achievement was used to inform a three-year learning recovery plan and to adjust the curriculum and teacher training programs. Several countries invested in improving teachers’ capacity for assessment-informed instruction — encouraging teachers to use questions, observations, class tests, and other measures to make daily decisions on the pace of lessons. Some countries continued investments in school report cards and dashboards, with a view to making learning data available in useable formats to key stakeholders such as system-level policymakers and administrators, school leaders, teachers, parents, and students. However, many countries faced barriers such as poor-quality data, a lack of data management protocols and systems, and failure to optimize report formats for usability.

To Prioritize teaching the fundamentals, both during the pandemic-related school disruptions and on return to in-person schooling, several countries adjusted the scope and quantity of subjects to allow sufficient time for the development of foundational schools. In some cases, school timetables and calendars were also adjusted. These types of changes were strengthened in some countries by ensuring to align the teaching and learning materials with the evidence on teaching and learning. For example, in Côte d’Ivoire, a new early grade reading program included adjustments to teaching and learning materials to include explicit phonics instruction, using a step-by-step model of instruction with ample student practice, and associated teacher training to ensure the program’s success.

To Increase the efficiency of instruction, including through catch-up learning, several countries focused on providing inputs to scaffold teaching, helping teachers to move toward more effective practices. This included structured pedagogy packages, ranging from fully scripted lesson plans for context in which most teachers have little training to lists of suggested classroom activities for contexts in which teachers are well trained. Some countries, such as Zambia, launched or continued investing in targeted instruction interventions to address situations of large heterogeneity of student achievement within classes. This involved grouping and regrouping students according to achievement levels for targeted instruction during part of the school day or year. Other approaches to improve efficiency of instruction by supporting struggling students included supplemental remediation, small-group tutoring, and adaptive and self-guided learning tools.

To Develop psychosocial health and wellbeing, given the detrimental impact of the pandemic on these, several countries made investments aimed at students and teachers. These included initiatives related to socioemotional learning, systems to identify students in need and referring them for specialized services, training related to teacher wellbeing, and providing specialist staff in schools. For example, in Colombia, a program designed to build empathy and self-regulation among primary school students, which was piloted in 2019, was scaled up nationally in 2021.