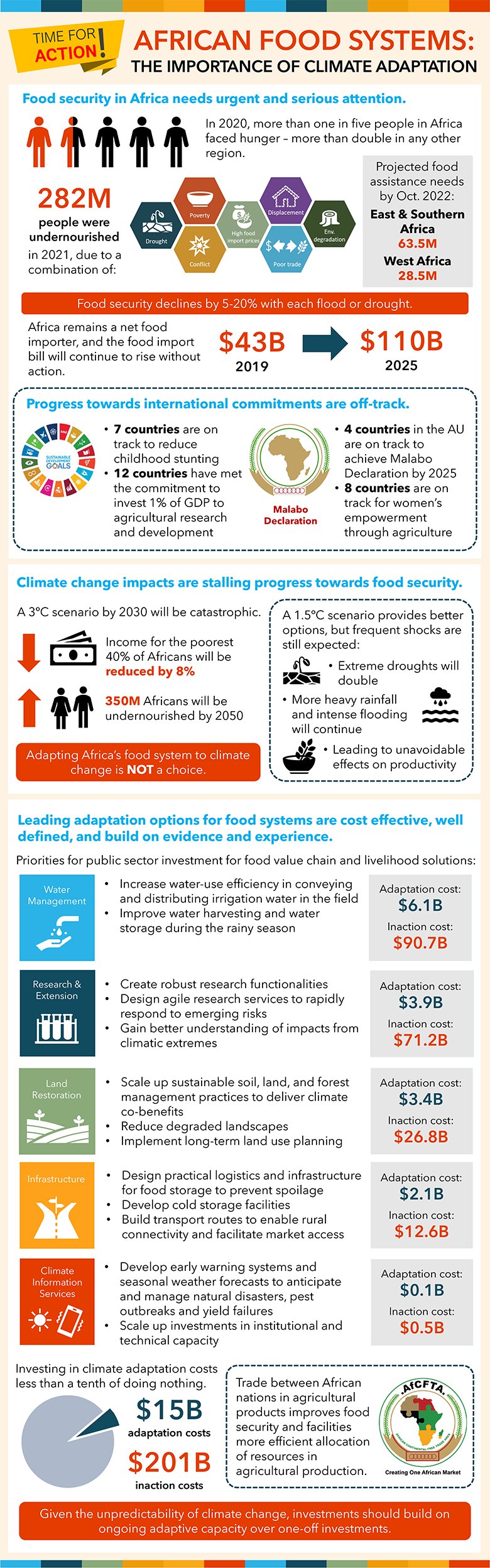

The infographic describes the importance of climate adaptation to African food systems. Food security in Africa needs urgent and serious attention. In 2020, more than one in five people in Africa face hunger. In 2021, 282 million people were undernourished due to a combination of drought, poverty, conflict, high food import prices, displacement, poor trade, and environmental degradation. It is projected that the number of people requiring food assistance by October 2022 will reach 63.5 million people in East and Southern Africa and 28.5 million in West Africa.

Food security declines by 5-20% with each flood or drought.

Africa remains a net food importer, and the food import bill will continue to rise without action from $43 billion in 2019 to $110 billion in 2025.

Progress towards international commitments are off track: 7 countries are on track to reduce childhood stunting; 12 countries have met the commitment to invest 1% of GDP to agricultural research and development; 4 countries in the AU are on track to achieve the Malabo Declaration by 2025; and 8 countries are on track for women’s empowerment through agriculture.

Climate change impacts are stalling progress towards food security. A 3 degree Celsius scenario by 2030 will be catastrophic. Income for the poorest 40% of Africans will be reduced by 8% and 350 million Africans will be undernourished by 2050.

A 1.5 degree Celsius scenario provides better options, but frequent shocks are still expected. Extreme droughts will double and more heavy rainfall and intense flooding will continue, leading to unavoidable effects on productivity.

Adapting Africa’s food system to climate change is NOT a choice.

Leading adaptation options for food systems are cost effective, well defined, and build on evidence and experience. The following are priorities for public sector investment for food value chain and livelihood solutions.

- Water Management. Increase water-use efficiency in conveying and distributing irrigation water in the field, and improve water harvesting and water storage during the rainy season. The estimated cost for adaptation is $6.1 billion while the estimated cost for inaction is $90.7 billion.

- Research and Extension. Create robust research functionalities, design agile research services to rapidly respond to emerging risks, and gain better understanding of impacts form climatic extremes. The estimated cost for adaptation is $3.9 billion while the estimated cost for inaction is $71.2 billion.

- Land Restoration. Scale update soil, land, and forest management practices to deliver climate co-benefits, reduce degraded landscapes, and implement long-term land use planning. The estimated cost for adaptation is $3.4 billion while the estimated cost for inaction is $26.8 billion.

- Infrastructure. Design practical logistics and infrastructure for food storage to prevent spoilage, develop cold storage facilities, and build transport routes to enable rural connectivity and facilitate market access. The estimated cost for adaptation is $2.1 billion while the estimated cost for inaction is $12.6 billion.

- Climate Information Services. Develop early warning systems and seasonal weather forecasts to anticipate and manage natural disasters, pest outbreaks and yield failures, and scale up investments in institutional and technical capacity. The estimated cost for adaptation is $0.1 billion while the estimated cost for inaction is $0.5 billion.

Investment in climate adaptation costs less than a tenth of doing nothing. Adaptation costs are estimated at $15 billion and inaction is estimated to cost $201 billion.

Trade between African nations in agricultural products improves food security and facilitates more efficient allocation of resources in agricultural production. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCTA) would help facilitate interregional trade.

Given the unpredictability of climate change, investments should build on ongoing adaptative capacity over one-off investments.