Across the world, persons with disabilities often face barriers that prevent them from accessing services, education, or employment opportunities. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated this risk and exposed some of the existing inequalities they face on a regular basis

An Accessible Future for Persons with Disabilities

What Does It Take?

120 kilometers south of Kigali, in a remote part of Southern Rwanda’s Huye District, lies the G.S. Kabuga school.

Warm sunshine—with the occasional drizzle of rain—greets students as they trickle into class on a Monday morning. Led by their class prefect and teacher, the kids assume their seats inside a spacious classroom with two large blackboards on opposing flanks. One learner, a wheelchair user, rolls up alongside a bench and shuffles in alongside a classmate.

“Children with disabilities are just like other children,” remarks Brother Jovite Sindayigaya, headmaster at the school. “The country needs them and so does the world in general. I get happiness from seeing them succeed.”

G.S. Kabuga is one of 3,388 schools in Rwanda that have benefitted from reconstruction and refurbishment efforts, funded by the government of Rwanda and the World Bank, with technical assistance provided by the Bank's Inclusive Education Initiative. In the span of just one year, 22,505 classrooms across all 30 districts of Rwanda were built or refurbished with some accessibility features for learners with disabilities.

Muhawenima Jaqueline, a young, female learner sits in her wheelchair wearing a blue shirt and skirt. She is surrounded by her classmates, all of whom are smiling.

Muhawenima Jaqueline, a young, female learner sits in her wheelchair wearing a blue shirt and skirt. She is surrounded by her classmates, all of whom are smiling.

“Previously, 3 or 4 students would have to share a single desk and kids would stumble on my son’s leg," says Jules Maurice Mwizerwa, whose son, Elie, has an under-developed foot.

“Now that the new classrooms have been built, there is no more squeezing. And he can use the improved toilets because he no longer has to squat.”

Meanwhile, ramps at the school entrance and the classrooms, added as part of the improvement project, provide more ease for wheelchairs users to access their classrooms.

Social components of this project are also being introduced to accompany the physical changes at schools across the country to ensure the sustainability of these improvements for years to come.

For example, teachers at G.S. Kabuga are now learning inclusive teaching methods as part of their mandatory, continuous professional development courses.

Reflecting on these trainings, one teacher reflected to how, for many teachers, perceptions have changed for the better:

“My advice to all teachers would be to change their behaviors and consider all children beneficial to the country's development and to their lives.”

G.S. Kabuga stands out as just one example of how to better empower learners with disabilities in order to help them reach their full potential.

The commitment by Rwanda to better ensure all students are given full access to education goes a long toward supporting learners with disabilities and their development needs and provides insights into tackling this global development challenge.

10 Commitments

on Disability-Inclusion

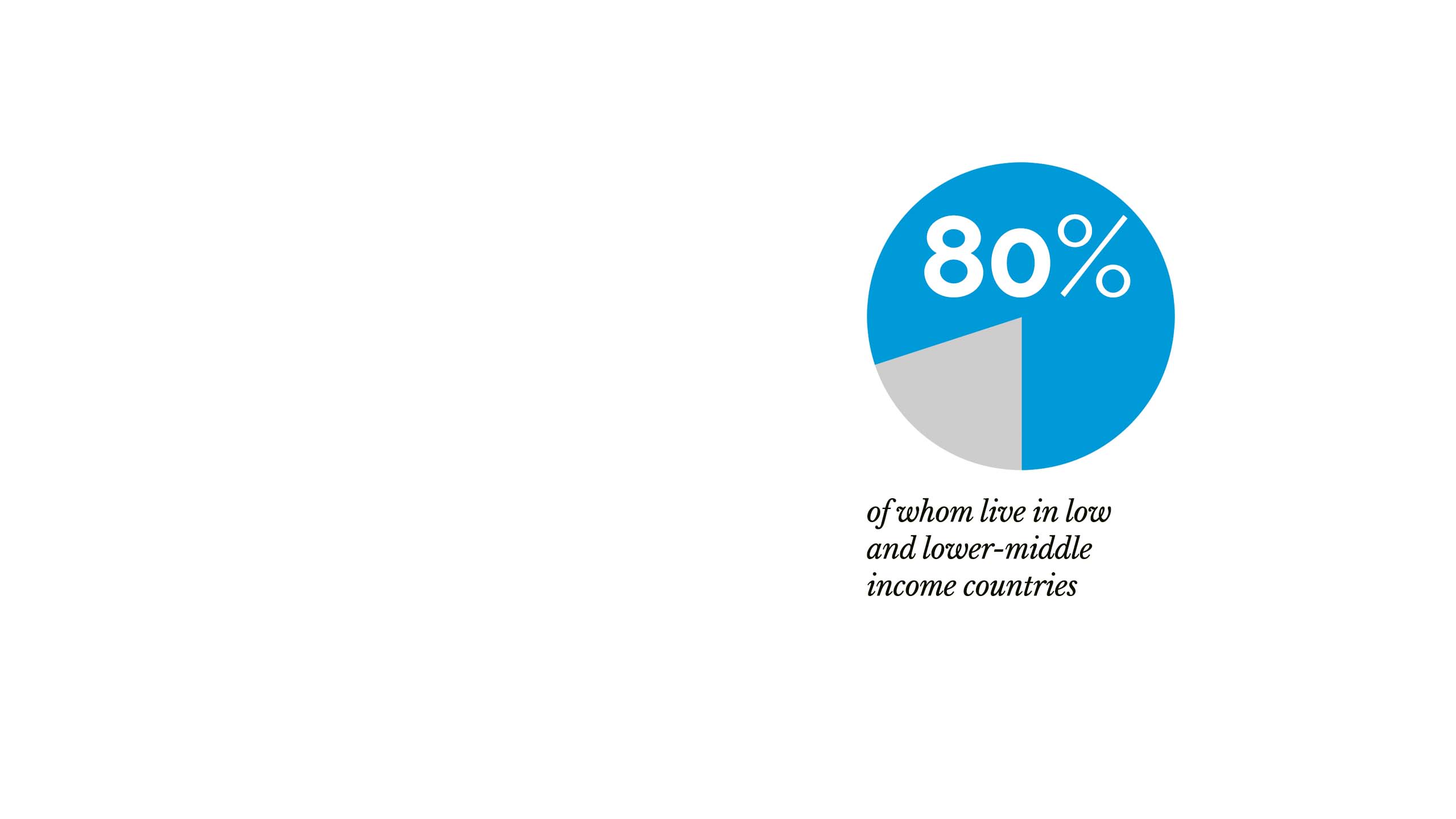

Today, one billion people have a disability – representing 15 percent of the world’s population, 80% of whom live in low- and lower-middle income countries. Their disability might be visible or invisible; it may be physical, cognitive, or sensory.

Across the world, persons with disabilities often face barriers that prevent them from accessing services, education, or employment opportunities. As a result, they are often not able to fully participate in the economy and are driven into poverty. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated this risk and exposed some of the existing inequalities they face on a regular basis.

There can be no effective poverty reduction if persons with disabilities are not participating in all stages of development programs.

In 2018, at the first Global Disability Summit, the World Bank Group made Ten Commitments across several sectors designed to accelerate global action for disability-inclusive development.

Despite global setbacks brought-on by the COVID-19 crisis, significant progress has been made in meeting these commitments, with three of the original having been achieved already.

Going into the second Global Disability Summit (2022), a few of the Commitments have been updated to further enhance the positive impact the World Bank Group is having on disability-inclusive development.

10 Commitments

on Disability-Inclusion

Today, one billion people have a disability – representing 15 percent of the world’s population, 80% of whom live in low- and lower-middle income countries. Their disability might be visible or invisible; it may be physical, cognitive, or sensory.

Across the world, persons with disabilities often face barriers that prevent them from accessing services, education, or employment opportunities. As a result, they are often not able to fully participate in the economy and are driven into poverty. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated this risk and exposed some of the existing inequalities they face on a regular basis.

There can be no effective poverty reduction if persons with disabilities are not participating in all stages of development programs.

In 2018, at the first Global Disability Summit, the World Bank Group made Ten Commitments across several sectors designed to accelerate global action for disability-inclusive development.

Despite global setbacks brought-on by the COVID-19 crisis, significant progress has been made in meeting these commitments, with three of the original having been achieved already.

Going into the second Global Disability Summit (2022), a few of the Commitments have been updated to further enhance the positive impact the World Bank Group is having on disability-inclusive development.

01: Inclusive Education

Ensuring all World Bank-financed education projects are disability-inclusive by 2025.

02: Technology and Innovation

Ensuring all World Bank-financed digital development projects are disability sensitive, including using universal design and accessibility standards.

03: Data Disaggregation

Build up the evidence base on disability inclusion through data collection, to inform good practice for policymakers globally.

04: Women and Girls

Analyze data on the socio-economic inclusion of women with disabilities in legal and policy frameworks by the Women, Business and the Law team to build evidence for better protection of the rights of women with disabilities in World Bank Group operations.

05: Post Disaster Reconstruction

Ensuring that all projects financing public facilities in post-disaster reconstruction are disability-inclusive.

06: Transport

Ensuring that all World Bank-financed urban mobility and rail projects that support public transport services are disability-inclusive by 2025.

07: Private Sector

Enhancing due diligence on private sector projects financed by the IFC regarding disability inclusion and strengthening IFC’s signaling on the importance of the private sector for disability inclusion in areas including education, transport, economic inclusion and disruptive technology among others.

8: Social Protection

Ensuring that 75 percent of World Bank-financed social protection projects are disability-inclusive by 2025.

09: Staffing

Fostering a more inclusive environment in the World Bank Group - by implementing the disability inclusion strategy.

10: Operationalizing

Promoting the updated Disability Inclusion and Accountability Framework among World Bank staff.

Disability and the

International Development Association (IDA)

The World Bank’s engagement in disability inclusion is a long standing one and the Ten Commitments provide the opportunity to systematically include persons with disabilities in projects and programs and prioritize the effective participation of persons with disabilities in World Bank Group activities.

Highlighting this commitment is the inclusion of disability as a cross-cutting theme in the current IDA19 financing package. The International Development Association (IDA) is the part of the World Bank that assists low-income economies.

The next financing package, the cycle for which beings in July 2022, will further scale-up support to disability inclusion across sectors.

Projects in education, health, social protection, water, urban, digital development, and transport will contain explicit actions to make core services accessible to persons with disabilities. These efforts will be grounded in the World Bank’s corporate framework and objectives on disability inclusion, in support of operationalizing the Environmental and Social Framework (ESF), the IDA19 policy commitments, the Ten Commitments on disability-inclusive development, and the Disability Inclusion and Accountability Framework.

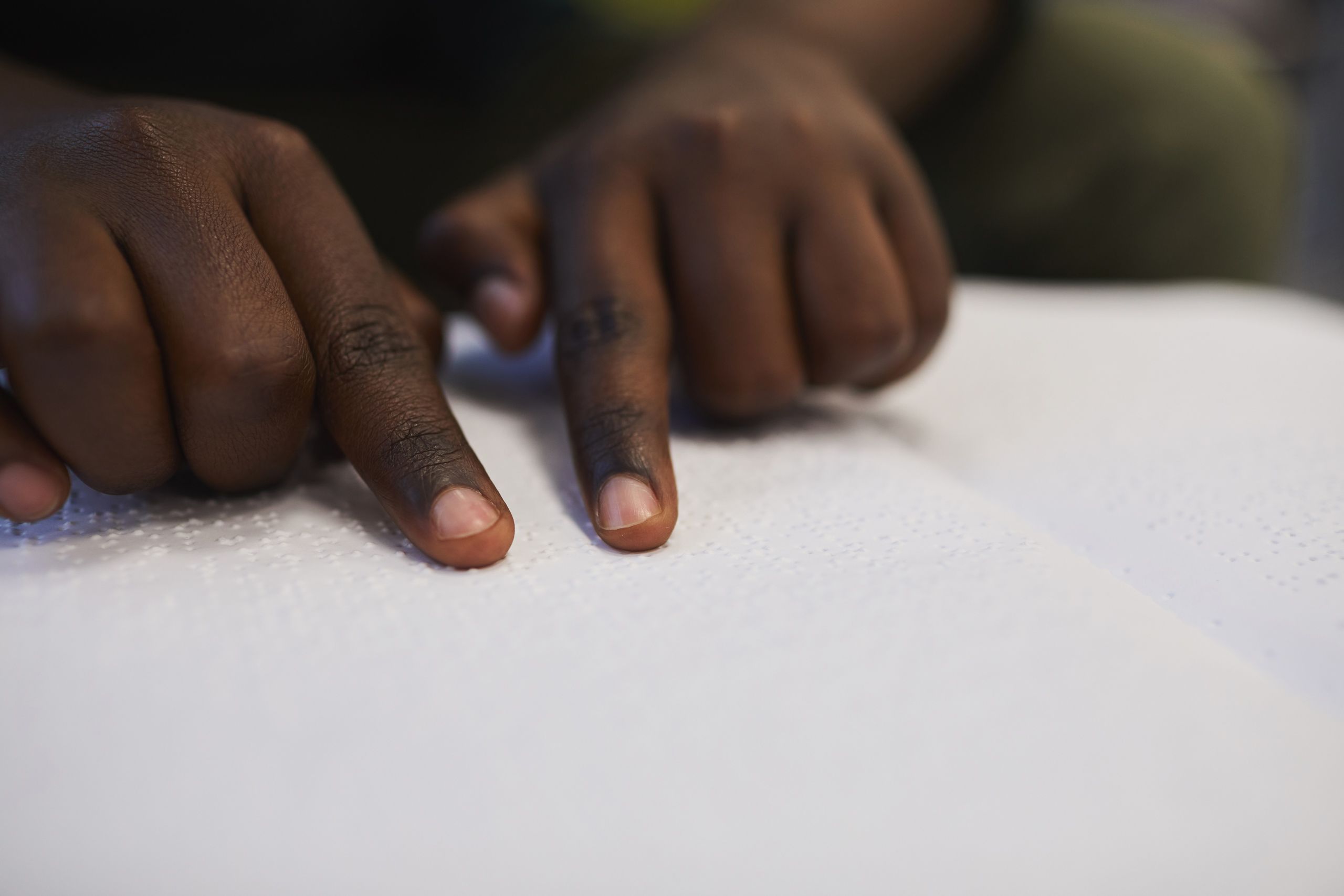

Photo credit for braille image: Shutterstock

Social Protection

in Ghana

Ghana’s Bongo district is situated in the far north of the country, on the border with Burkina Faso.

Moses Apitaaba Azubire sits in his courtyard weaving a basket. His hands move quickly, creating intricate and colorful patterns of yellow, blue, and red, while young chicks chase each other around him.

Moses is blind. He permanently lost his vision several years ago due to an illness. He was able to rebuild his livelihood through support he received from the Ghana Social Safety Nets Project. Through this IDA-funded project, extremely poor households, such as Moses’, receive bi-monthly cash transfers to support him and his household.

“We were advised to complete one cycle of weaving a basket for sale and use the proceeds to buy additional straw to continue weaving while our grants were being processed,” remembers Moses.

Moses was also able to enroll into the productive inclusion program that supports creating sustainable livelihoods. This program includes training, a one-time, start-up grant, and coaching.

The program makes a concerted effort to include persons with disabilities by identifying small, viable enterprises they can partake in.

Moses was trained in basket weaving for a week, after which he was given the remaining straw from the training to practice his newly acquired skill.

“We were advised to complete one cycle of weaving a basket for sale and use the proceeds to buy additional straws to continue weaving while our grants were being processed,” remembers Moses.

Persons with disabilities, especially in developing countries, are often among the most vulnerable. Social safety nets are therefore essential in supporting their productivity and reducing the gaps between persons with and without disabilities. The World Bank has committed that to 75 percent of financed social protection projects will be disability-inclusive by 2025.

Through the selling of the baskets he makes, Moses was able to save, invest, and support his wife and children.

"As we speak now” he says, “one of my children was able to complete secondary school in 2020 whiles the other is still pursuing second cycle education.”

Social Protection

in Ghana

Ghana’s Bongo district is situated in the far north of the country, on the border with Burkina Faso. Moses Apitaaba Azubire sits in his courtyard weaving a basket. His hands move quickly, creating intricate and colorful patterns of yellow, blue, and red, while young chicklets chase each other around him.

Moses is blind. He permanently lost his vision several years ago due to an illness. He was able to rebuild his livelihood through support he received from the Ghana Social Safety Nets Project. Through this IDA-funded project, extremely poor households such as Moses’, receive bi-monthly cash transfers to support him and his household.

Moses was also able to enrol into the productive inclusion program that supports creating sustainable livelihoods. This program includes training, a one-time, start-up grant, and coaching. The program makes a concerted effort to include persons with disabilities by identifying small, viable enterprises they can partake in.

Moses was trained in basket weaving for a week, after which he was given the remaining straw from the training to practice his newly acquired skill.

“We were advised to complete one cycle of weaving a basket for sale and use the proceeds to buy additional straw to continue weaving while our grants were being processed,” remembers Moses.

Persons with disabilities, especially in developing countries, are often among the most vulnerable. Social safety nets are therefore essential in supporting their productivity and reducing the gaps between persons with and without disabilities. The World Bank has committed that to 75 percent of financed social protection projects will be disability-inclusive by 2025.

Through the selling of the baskets he makes, Moses was able to save, invest, and support his wife and children.

“As we speak now,” he says, “one of my children was able to complete secondary school in 2020 whiles the other is still pursuing second cycle education.”

Transport

in Latin America

Expanding access to quality education, skills, and jobs is critical. But to make the most of these opportunities, persons with disabilities need to be able to access them.

This is why all World Bank-financed urban mobility and rail projects that support public transport services will be disability-inclusive by 2025.

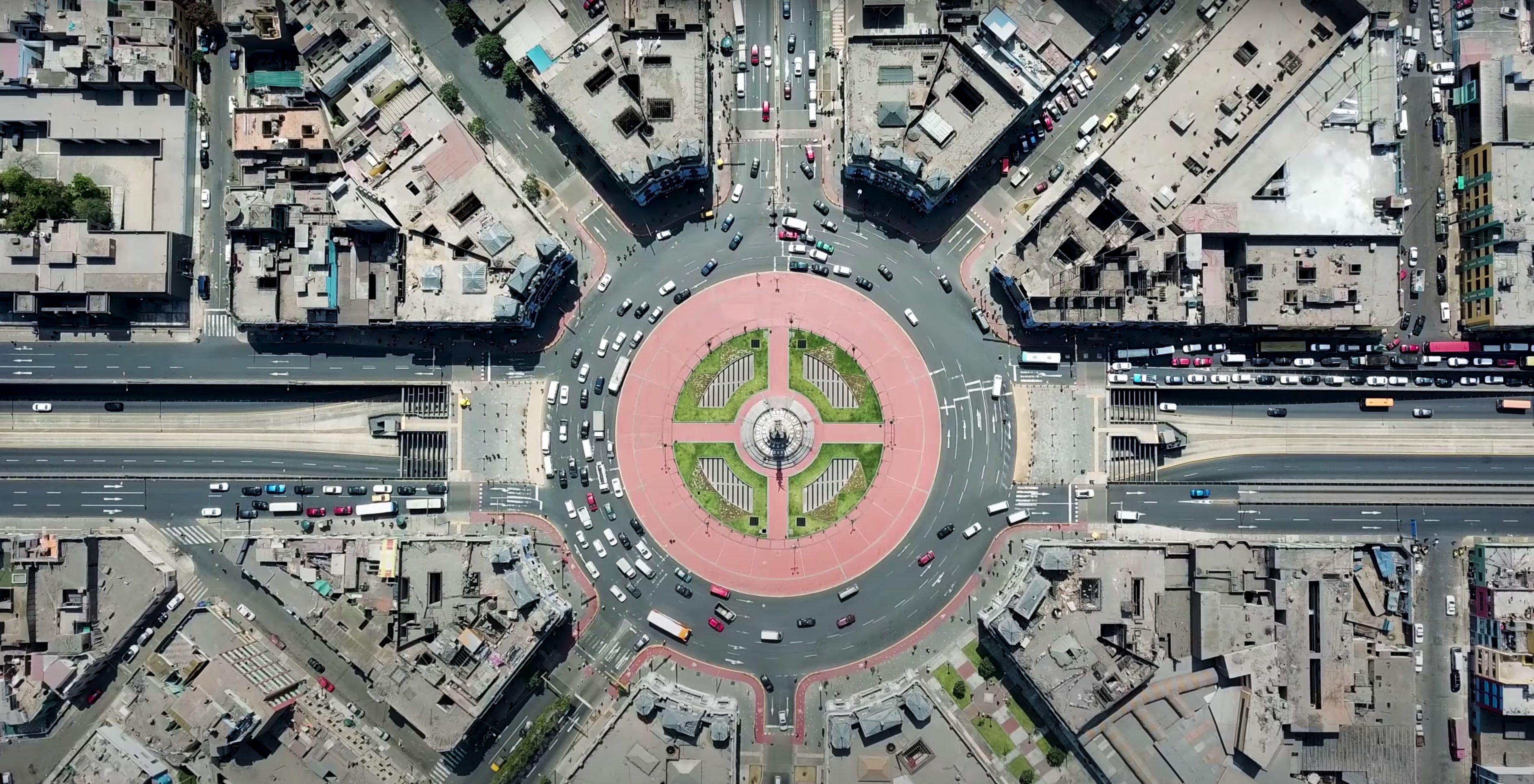

In Peru’s bustling capital city, Lima, the Metropolitano, a Bus Rapid Transit system (BRT), faced accessibility challenges. While stations and buses incorporated accessibility features, the surrounding streets and public spaces were poorly adapted for use by persons with disabilities.

“I took one of the Metropolitano buses because I thought it was accessible to everyone, but I fell! I believe that this incident, although negative, was also positive because it made people aware of a major need for change in this transit system.”

A grant from the Japanese government, administered through a World Bank Trust Fund, paved the way for the rehabilitation of the area surrounding one of Lima’s major central stations: Plaza Dos de Mayo.

The participation of organizations of persons with disabilities throughout the project made it possible to identify the main problems in their access to the Metropolitano.

“Tactile paving surfaces are vital because blind people use the Metropolitano a lot,” stressed Ruiz.

“The access ramps are wonderful, and I don’t have to make an effort anymore to cross. Anyone can move with total freedom.”

Even before the Plaza Dos de Mayo pilot project was completed in 2017, the municipality of Lima took on the new accessibility standards and applied them in the rehabilitation of other stations across the city beyond the BRT. The expansion of the Northern part of the BRT line, currently under construction with financing from the World Bank, is incorporating universal accessibility standards based on lessons learned from the Plaza Dos de Mayo revamp.

Across the border in Colombia, a cable car system called TransMiCable is connecting the residents of Bogotá’s poorest neighborhoods to services and jobs.

The cable car has provided the residents of Ciudad Bolívar with an increased sense of safety, a reduced commute time, and job opportunities. In addition, the fully accessible infrastructure has made it much easier for wheelchair users to get around.

“Here, we take priority, and people do respect us,” says Alexander Garcia, 35, who uses a wheelchair.

The International Finance Corporation (IFC), the arm of the World Bank Group that focuses on the private sector in developing countries, has supported the TransMiCable cable car and related TransMilenio bus system as part of a financing package to the City of Bogotá. The investment followed a three-year advisory program through the IFC’s Cities Initiative that aimed to improve the project’s environmental and social standards.

Water and Sanitation

in Indonesia

So, what does it take to design and implement development programs that are truly disability-inclusive?

Persons with disabilities are a large and diverse population group and there can be no “one-size-fits-all” approach. Bright lights that help a person who has low vision may not be appropriate for someone with autism, for instance.

Another critical point is that disability-inclusive interventions rely not only on infrastructure, but also on training, awareness-building, and having the right guidelines in place.

This dual approach is one of the factors that contributed to the successful integration of disability-inclusion into Indonesia’s National Rural Water Supply and Sanitation Project (PAMSIMAS).

This long-running project has helped Indonesia’s low-income rural and peri-urban population access improved water supply and better sanitation facilities.

Since the start of the project, PAMSIMAS has used a community-driven development approach for planning, constructing, and monitoring water and sanitation services. And when it came to ensuring that the infrastructure design was universally accessible, the project involved persons with disabilities at every step.

In addition, villagers, community facilitators, and central and local government officers were trained to better understand the importance of disability inclusion.

Today, 10,676 villages across the country have disability-inclusive facilities - including spacious school toilets with wider doors and higher water closets, handrails, non-slippery floors, tactile paving, signs, and ramps.

These improved facilities are benefiting a wide range of people, from pregnant women to persons with functional disabilities, the elderly and young children.

All images in this section are credited to: Pamsimas program, Ministry of Public Work and Human Settlement, Indonesia.

Towards More

Inclusive Societies

Back in Rwanda’s Huye District, the school bell tings at G.S. Kabuga. Monday’s lessons have ended, and the classroom begins to buzz with chatter from the students. A warm evening breeze greets them as they descend into the schoolyard and make their way home.

“When children go through your wings and prosper to bring their contribution to the country, it is the best thing ever.”

For learners of all abilities, centering inclusion at the heart of their education has paved the way for brighter futures. The World Bank is a global partner in the promotion of equal opportunity for persons with disabilities.

To foster societies that are truly inclusive, a more complete approach must always be taken. Investments are needed across the full spectrum of society...

...from accessible public transport to resilient social safety nets and beyond.

Related Links:

- Disability Inclusion at the World Bank

- Social Sustainability and Inclusion at the World Bank

- International Development Association and Disability Inclusion

- World Bank Group Commitments on Disability-Inclusive Development

- International Development Association (IDA)

Read Past In-Depth Stories:

- Stepping Up: Ensuring the Poorest are Not Left Behind

- Country on a Mission: The Remarkable Story of Bangladesh’s Development Journey

- Heeding the Call of a Country in Crisis: IDA in Yemen

- Explore all stories

Video and Photo credits: World Bank Group unless otherwise noted.

Twagiramariya Aurélie, a teacher at G.S. Kabuga school, sits smiling in her classroom. She wear an ocean-blue dress and a hairband.

Twagiramariya Aurélie, a teacher at G.S. Kabuga school, sits smiling in her classroom. She wear an ocean-blue dress and a hairband.

Towards More

Inclusive Societies

Back in Rwanda’s Huye District, the school bell tings at G.S. Kabuga. Monday’s lessons have ended, and the classroom begins to buzz with chatter from the students. A warm evening breeze greets them as they descend into the schoolyard and make their way home.

Twagiramariya Aurélie, a teacher at G.S. Kabuga school, sits smiling in her classroom. She wear an ocean-blue dress and a hairband.

Twagiramariya Aurélie, a teacher at G.S. Kabuga school, sits smiling in her classroom. She wear an ocean-blue dress and a hairband.

“When children go through your wings and prosper to bring their contribution to the country, it is the best thing ever.”

For learners of all abilities, centering inclusion at the heart of their education has paved the way for brighter futures. The World Bank is a global partner in the promotion of equal opportunity for persons with disabilities.

To foster societies that are truly inclusive, a more complete approach must always be taken. Investments are needed across the full spectrum of society...

...from accessible public transport to resilient social safety nets and beyond.

Related Links:

- Disability Inclusion at the World Bank

- Social Sustainability and Inclusion at the World Bank

- International Development Association and Disability Inclusion

- World Bank Group Commitments on Disability-Inclusive Development

- International Development Association (IDA)

Read Past In-Depth Stories:

- Stepping Up: Ensuring the Poorest are Not Left Behind

- Country on a Mission: The Remarkable Story of Bangladesh’s Development Journey

- Heeding the Call of a Country in Crisis: IDA in Yemen

- Explore all stories

Video and Photo credits: World Bank Group unless otherwise noted.