One of the challenges for social inclusion in development projects is to make the potential benefits accessible to the most vulnerable. In a country as diverse and vast as Brazil, adaptive, flexible, and innovative approaches are necessary, built participatively from local realities.

Challenges range from the size of the territory to internet access, with only 22% of Brazilians aged 10 and older having satisfactory connectivity. This adds to the inequality in education access, with half the population over 25 lacking a high school diploma. Particularly in rural areas, where 15% of Brazilians aged 16 to 29 lived, this number rises to 24.8% in the Northeast, the highest in the country.

The rural exodus, especially among the youth, is a major sustainability challenge. Brazil’s rural population reduction is nearly double the global average, with a 33.8% reduction between 2000 and 2002, compared to the global 19.2%.

This context led the Ceará Rural Development and Sustainable Competitiveness Project Phase II, known as São José IV, to identify major barriers to youth inclusion and promoting sustainable social development opportunities.

The Rural Youth Call

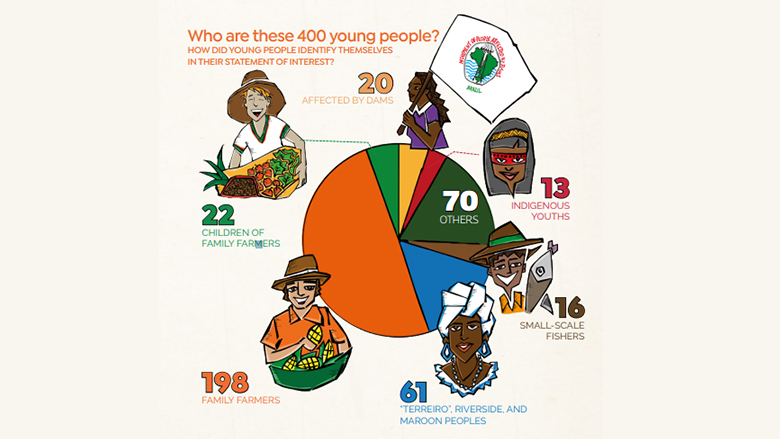

In 2020, a series of actions were designed exclusively for rural youth, particularly in family farming, considering gender and other priority groups like Indigenous Peoples, quilombolas, black people, artisanal fishers, and others traditional communities.

The outcome was a pioneering social inclusion initiative: the Rural Youth Call, supporting non-agricultural activities and fostering youth leadership by directly transferring resources to young people without intermediaries. Historically, rural projects in Brazil support producer organizations and cooperatives collectively.

The strategy was organized in three stages. The first involved registration and expression of interest. Four hundred were selected for the second phase, which included training in entrepreneurship, project planning, and management for agricultural and non-agricultural projects. Finally, 297 intervention projects were chosen among those who completed the training.

Intervention projects received technical and financial support, with up to US $3,000 disbursed per project. 286 youths completed all three stages of the call. The Rural Youth initiative invested US$ 900,000 in individual youth projects that finished the training and developed viable investment projects.

By providing direct funding to individual initiatives, the call became a transformative tool, capable of changing these youths’ perspectives on life, seizing opportunities, and believing in their dreams.

That was how Victor Alan, 24, ended up on the runways of São Paulo Fashion Week 2024 featuring his filé lace art in the Catarina Mina brand collection. After receiving support from the Rural Youth Call, Victor invested in his art. He is one of the few artisans still working with filé lace, an ancient and laborious technique.