In the heart of São Paulo, at Luz Station during the lunch rush, a young boy named Breno Xavier, age 11, stands on the platform with his cellphone at the ready, eager to capture the moment the Line 4 (yellow) subway train arrives. The platform is equipped with safety doors made of thick glass, eliminating the danger of falling onto the tracks. These doors only open when the train, which runs without a driver, comes to a halt. This line boasts the highest level of automation in all of Latin America.

"Mom, can you cover my ears?" Breno asks his mother, Paula Xavier.

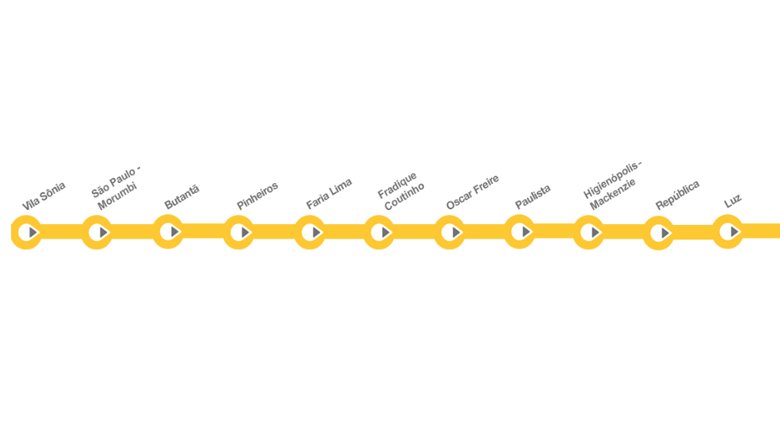

Breno, who is mildly autistic and sensitive to loud noises like the screech of the subway's brakes, is also deeply fascinated by trains, especially Line 4. Every week, he and his mother journey from their home in the city's northwest to Vila Sônia in the west, traveling downtown to ride the full length of the yellow line and back, before heading to the north for Breno's therapy sessions. On these driverless trains, Breno indulges in his favorite fantasy of being the conductor.

"It's his favorite activity," Paula shares. "He's collected subway maps from all over the city and has even gotten his friends excited about them."

Breno and Paula's story is just one example of how Line 4 is more than a means of transportation for commuters, students, tourists, and others—it's a place where memories are made.