The recent history of the Dominican Republic is, in many aspects, a success: exceptional economic growth compared to the rest of the region, a middle class outnumbering the poor, and improvements in the quality of life. However, when focusing on Dominican girls and women, the story does not seem to be the same.

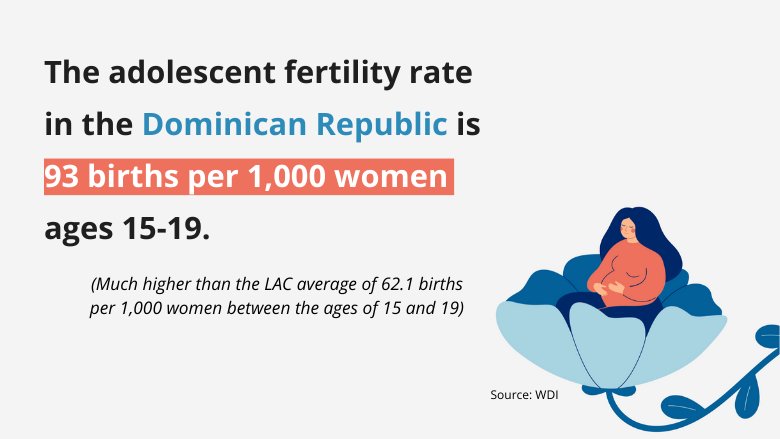

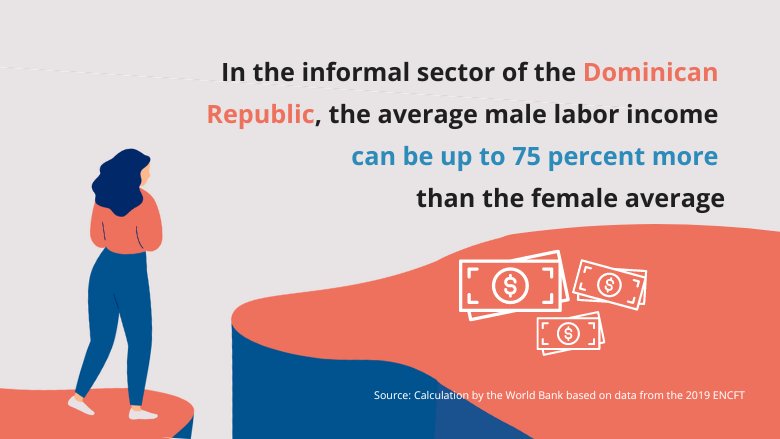

On one hand, the pace of poverty reduction has not been proportional to economic growth, and women are one of the most affected groups, being in a more vulnerable situation than men. On the other hand, beneath the economic indicators, inequalities between genders persist, often accentuated by existing social norms.

“Staying in the classroom and finishing school is one of the most critical and determining factors for the future of Dominican women,” explains Alejandro de la Fuente, Senior Economist at the World Bank and one of the authors of the World Bank's Dominican Republic Gender Assessment.