Are climate change and drought connected? We asked Richard Damania, the World Bank’s Chief Economist for Sustainable Development, and two experts from the Bank’s Sustainable Development unit: Senior Economist Esha Zaveri and Senior Climate Change Specialist Nathan Engle. The three are authors of the paper, Droughts and Deficits: Summary Evidence of the Global Impact on Economic Growth.

Is drought increasing and is climate change to blame?

Water deficits are fast becoming the new normal. Over the last half century, extreme “dry rainfall shocks” – i.e., below-average rainfall -- have increased 233% in certain regions. A dry shock that is one standard deviation from the norm is normally a rare event that could be expected to include 15 of the driest episodes in a century. A dry shock that is two standard deviations from the norm is even rarer and includes the driest 2.5 years in a century. Such dry episodes should be intermittent, but they are occurring more frequently. At the same time, areas with above-average

rainfall are in decline.

Our empirical observations are consistent with other scientific projections that by the late 21st century the land area and population facing extreme droughts could more than double globally. While projections of future rainfall are highly uncertain, climate change models are unanimous that rainfall will become more erratic and extreme with rising temperatures.

Over the last half century, extreme “dry rainfall shocks” – i.e., below-average rainfall -- have increased 233% in certain regions.

Where are dry shocks happening and who is most affected?

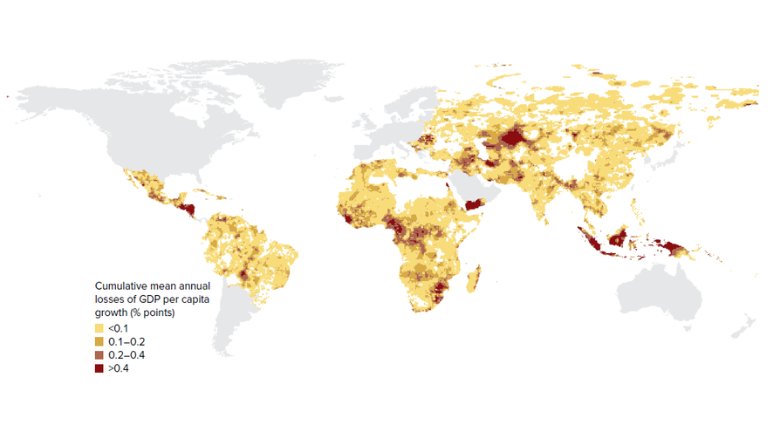

Geography and income levels matter. The impacts are unequal. Poor countries that are typically in arid and semi-arid regions experience more dry shocks and are also more vulnerable to these shocks. In Somalia, for example, rainfall in the 2022 March-to-May season was the lowest in the last six decades. Large parts of Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda have also experienced very dry conditions compared with the average. Drought conditions in eastern Ethiopia, northern Kenya, and Somalia led the United Nations to warn that some 22 million people could be at risk of starvation in 2022.

A similar drying pattern is not found in higher income countries that are typically in temperate and moist areas, where rainfall has also become significantly more variable over the past five decades. Europe experienced two exceptional droughts in 2018 and 2019 that scientists called unprecedented in the last 250 years. At the other end of the spectrum, July 2021 brought both record-breaking rainfall and severe floods to Europe; that same month, torrential rain led to devastating floods in Henan province, China, forcing more than 1 million people to relocate.

In general, the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report warns that the collision of extreme events will only become more frequent. Adapting to this increasing variability can be challenging because of the unpredictable duration of a deviation, its uncertain magnitude, and its unknown frequency.

In Somalia, rainfall in the 2022 March-to-May season was the lowest in the last six decades.

How are dry shocks affecting poverty?

Dry shocks are especially harmful to economic growth in developing countries. Compared to normal conditions, moderate drought reduces growth in developing countries, on average, by about 0.39 percentage points, while extreme drought reduces growth by about 0.85 percentage points. In a scenario where overall growth is below 3%, even moderate shocks could cause a growth slump. Wet shocks, in contrast, have little impact on GDP growth in developing countries.

Beyond GDP, droughts can widen the poor-rich gap in low- and middle-income countries, with significant and long-term impacts on farms, firms, and families. A dry shock in the first 1,000 days of a child’s life can affect their future prospects. In rural Africa, women born during severe droughts grow up physically shorter, receive less education, and ultimately, become less wealthy. The legacy of droughts can ripple through generations, harming not just the women who experienced them, but also their children, who are more likely to suffer from malnutrition.

Beyond GDP, droughts can widen the poor-rich gap in low- and middle-income countries, with significant and long-term impacts on farms, firms, and families.

Climate change is expected to lead to greater drought severity in most regions, so without significant improvements to how policy makers manage droughts, the world is on a path to even greater losses in economic growth and development gains due to these prolonged dry shocks.