Since 1990, global trade has increased incomes by 24 percent worldwide, and by 50 percent for the poorest 40 percent of the population. This growth has lifted more than 1 billion people out of poverty. Trade has also played a pivotal role in shaping the global economy and promoting positive socioeconomic outcomes.

Today, however, protectionist measures are on the rise. And trade tensions and geopolitical challenges are raising concerns about the trajectory of globalization.

As a result, deglobalization—the process of reducing global economic interdependence—has been at the forefront of current policy discussions. At a recent Policy Research Talk, World Bank Research Manager Daria Taglioni discussed the fundamental transformations taking place in the global trading system and how they relate to patterns of industrial organization. Moves toward regionalization, reshoring, or other forms of deglobalization threaten the intertwined facets of the modern economy: economic complexity and interdependence. Preserving their benefits in terms of economic growth, poverty reduction, and technological innovation in the face of an increasingly fractured system of global economic governance presents one of the most challenging terrains for trade policy in decades.

To illustrate the complexity at the heart of current global patterns of trade, Taglioni pointed to three apparent paradoxes. First, China has become ever more central to global trade networks in recent years, even as the United States and China engaged in a trade war. Second, despite shocks emanating both from policy and the COVID-19 pandemic, global value chains (GVCs) now account for an even greater proportion of global trade flows. In 2022, GVCs accounted for 52 percent of global trade, up from approximately 48 percent in 2015 and even slightly higher than prior to the 2007-2008 global financial crisis. And third, firms continue to connect with customers and suppliers all around the globe rather than just in their region, even as the challenges to global trade mount.

Given the breadth and depth of global interdependence, Taglioni argued that naïve trade and investment policies have significant unintended consequences. The goals that drive protectionist measures could be better achieved through increased rather than reduced international openness and cooperation, she said.

Trade Policy Meets the Law of Unintended Consequences

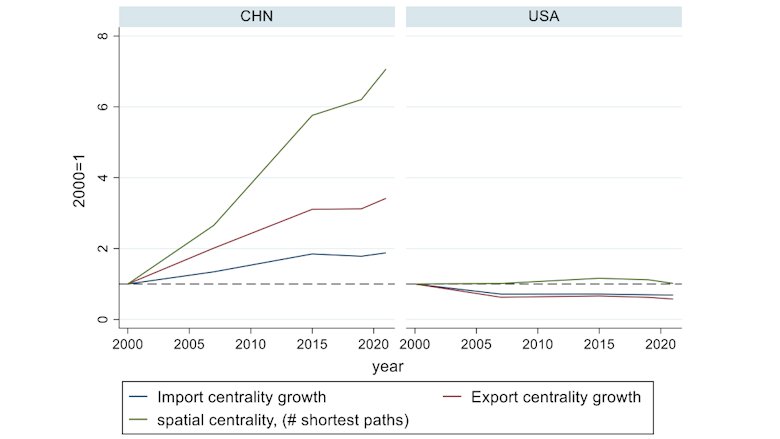

Economic paradoxes can often be accounted for by the law of unintended consequences. Recent trade policy is no exception. Consider the 2018-2019 US-China trade war, which ultimately affected around $450 billion in annual trade. As expected, the trade war reduced US exports to China and Chinese exports to the US. But China’s importance to global trade has only increased (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Growing Centrality of China in Global Trade

Notes: Calibrated to the year 2000, these charts compare the importance of China and the US to global trade over the past 20 years. For China, import centrality, export centrality, and spatial centrality—which is a measure of where global trade happens—have increased. The marked increase in China’s spatial centrality is closely tied to Asia’s development into an engine of global trade.

Third-party countries also saw their global exports increase as a result of the US-China trade war. Taglioni and her co-authors found that the implementation of protectionist policies during the US-China trade war led to a “bystander effect,” where US-China decoupling created opportunities for other countries not only to occupy the gap left by American and Chinese imports but also to expand their global exports. Bystander countries were able to benefit from economies of scale to increase their exports even beyond the gap initially left by the US-China trade war. Consequently, these protectionist actions resulted in an expansion of trade opportunities for many countries in the world, rather than a mere reallocation of market shares or a reduction of global trade.

The unexpected impacts of the US-China trade war highlight the complex interplay between protectionist policies, patterns of trade, and country-specific factors. Standard explanations of the effects of policy changes—factors like pre-existing patterns of product specialization—are no longer adequate. Instead, country-specific reforms and institutions that support productivity and flexibility are taking center stage in explaining export performance in this new era of globalization. Any attempt to confront the risks in the current global trading system will need to grapple with this level of complexity.

Trends in Global Trade Policy Are a Study in Contradictions

Despite the US-China trade war and other shocks to global trade in recent years, global trade has remained resilient. “Increasingly, headlines in the news suggest the world has turned protectionist. However, when we look at the policy data, we actually see contrasting trends,” said Taglioni.

Against a backdrop of increasing protection, many countries are at the same time pursuing deeper trade integration and international cooperation. While detrimental policies have been outpacing trade-liberalizing policies in recent years, the future is highly uncertain as researchers continue to work on identifying what is driving these trends.

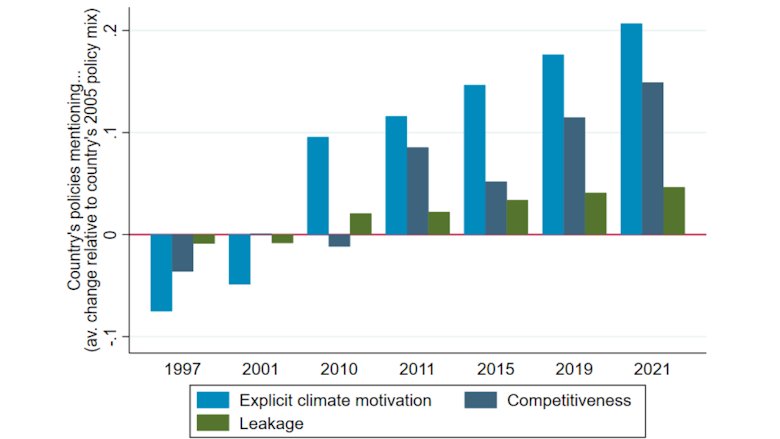

Forthcoming research from Taglioni and a team of researchers is examining one factor that has been gaining in importance: climate policy. Initial findings based on a new World Bank-Australian National University database of trade-related climate policies in G20 countries point to a dramatic growth in such policies (Figure 2). However, research to date has not concluded whether on balance these policies have hindered or helped trade.

Figure 2: The Number of Trade-related Climate Policies Has Increased Exponentially in G20 Countries

Notes: A new World Bank-Australian National University Climate Policies Database containing 1,800 distinct policies surveyed in G20 countries, with >1,500 in force as of March 2023, shows exponential growth in the number of trade-related climate policies. Selected dates on the x-axis mark COP meetings and other notable events (Kyoto, Bonn COP, Cancun COP, Paris, Trade War, Post Covid). Source: Aisbett et al., "The Implications of Climate Policy for Trade: Evidence from the Trade-related Climate Policy Database," work in progress.

Another area with clearer results is services trade regulation, which has become decidedly less restrictive since the global financial crisis. And at the broadest level, countries continue to show a commitment to trade with countries steadily signing more and deeper trade agreements over the last three decades.

Policies Aimed at Deglobalizing Could Be Costly and Counterproductive

Although the data show that recent trends in trade policy have been mixed, policies aimed at deglobalization still appear attractive in the face of mounting political tensions and fears of exposure to trade risks—especially with vital sectors of the economy at stake.

Recent estimates from international organizations have tried to quantify the costs of decoupling US-China trade and dividing the world into economic blocks. A recent working paper from the IMF estimates a GDP loss of 5 percent, while researchers at the WTO estimate a 12 percent welfare cost. However, Taglioni warned that these estimates are highly uncertain and very likely significantly underestimate the costs of decoupling.

In many cases, the complex supply chains that have developed over decades cannot be easily replaced, especially for industries relying on specialized inputs or global networks. Estimates of the costs of decoupling increase after accounting for the risk that some critical industries may be unable to function if the current global trade system were to be overturned. Thus, it is crucial to consider not only the potential economic costs but also the risks associated with disrupting critical industries and global supply chains in a deglobalized scenario.

A prime example of a critical industry which could be severely impacted is smartphones. Through the mapping of key component producers, Taglioni and her co-authors found that the production of smartphones is fundamentally global in nature. In digitally intensive industries, the way firms behave has been termed a Massively Modular Ecosystem—a decentralized system where incentives between firms are aligned and where geographically dispersed clusters of firms specialize in producing specific components of a device. This kind of industrial organization stands in stark contrast to older industries where a lead firm or handful of firms might dominate an entire sector.

The Massively Modular Ecosystem achieves remarkable economies of scale and promotes an efficient globalized trade system. However, being so interconnected also entails risks. Partial decoupling from this ecosystem would lead to substantial costs, and full decoupling could be fatal to an industry. A country aiming for self sufficiency would have to invest extraordinary amounts of capital and pay significant additional costs from efficiency losses.

Stepping back to draw out key policy lessons, Taglioni argued that even in a world where global trade carries risks, deglobalization is not necessarily an optimal policy response. As countries participate in global value chains, exposure to shocks that come from the global economy increases. At the same time, decoupling increases the exposure of an economy to local shocks, and Taglioni’s research has found that in most cases output is less volatile from shocks originating from GVCs rather than non-GVCs. Research also shows that more interconnected firms have better economic performance, even in periods of turbulence.

“In trade discussions, regulators need to appreciate that specialization and scale characterize the modern economy,” said Taglioni. In a global economy where industries thrive through deep specialization and large economies of scale, the benefits of coordination are large. This highlights the need to address the international tensions that have been dominating the international trade agenda.

“The problem is not too much globalization, but excessively narrow regulation. It is more important than ever to come to a new consensus on a global set of rules that extend beyond trade, i.e. on taxes and competition policies, data flows, critical infrastructure, and security, that all countries can comply with and benefit from,” Taglioni concluded.