Indigenous peoples make up 8 percent of the Latin American population but safeguard a fifth (22 percent) of the territory. Most of the areas where indigenous people live are critical from the standpoint of resistance to climate change: tropical forests, semi-arid woodlands, deserts, the Andean altiplano and rich coastal ecosystems. Young indigenous people are the first line of defense against climate change, given that their communities, despite contributing least to the problem, are among the most affected by it.

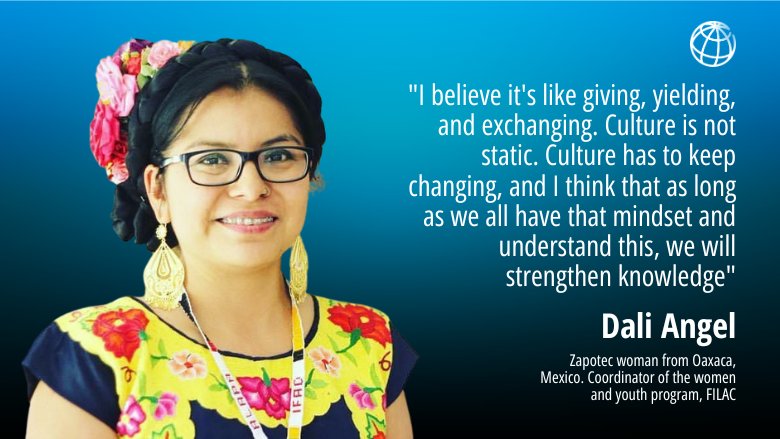

According to Dali Angel, a Zapotec woman from Oaxaca, Mexico: “It's the new generations that are able to bring their lives into dialogue within the globalized, capitalist, and new technological world, along with the preservation of the knowledge unique to indigenous peoples.” After years of promoting indigenous youth programs in the region, Angel currently coordinates the women and youth program of the Technical Secretariat of the Fund for the Development of Indigenous Peoples of Latin America and the Caribbean (FILAC).

In a virtual conversation, Angel spoke about the new program "Voices of Indigenous Youth for Action on Climate Change" (Voces de las Juventudes Indígenas para la Acción por el Cambio Climático), which will provide training for 90 young people from indigenous communities in the region. This initiative, supported by the World Bank and managed by FILAC in collaboration with the Universidad Autónoma de México, the Universidad Indígena Intercultural, the Red de Jóvenes Indígenas (RJI), the Foro Indígena de Abya Yala (FIAY) and the Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, seeks to strengthen the capacity of indigenous youth throughout the region to play a more active role in the climate agenda pursued by their own countries and communities.

The program is not confined to providing information, rather it is jointly designed as a collaborative venture. The participating universities, the RJI and the FIAY, under the leadership of FILAC, will ensure that the modules include both Western knowledge and the traditional knowledge of the indigenous peoples, drawing particular attention to instances where the two types of knowledge are complementary.

What does designing the program jointly mean, that is, taking into account both traditional knowledge and Western knowledge?

I am at present part of a course and a professor of chemistry with a doctorate has just arrived. We discuss climate change from a scientific point of view. While this view is important, is also vital to know the other side of the story. Scientists also need to know, respect, and respond to the knowledge embedded in the culture of indigenous peoples. It is clear there are two aspects to this: neither we nor they have knowledge of everything. The question is how can we combine the two types of wisdom and knowledge?

As indigenous peoples it is important for us to recognize that we have certain practices that are not necessarily our own. These are practices that we may have adopted and appropriated and that must be capable to change. When talking about climate change, land and territory, for example, we cannot detach these topics from the rights of indigenous women and young people, given that we have our own specificities and characteristics. To me, it is of no use, talking about climate change when the rights of indigenous women are being violated within our own community.

Why should indigenous youth be educated and trained?

A friend of mine who works at a foundation told me many years ago “Dali, it's not enough to be indigenous. You must acquire other tools if you want to get on in this world.” I said to myself straightaway: “But why, if being Zapotec is good enough for me?”. But that's not the point at all. We must learn, we have to acquire new tools, we have to strengthen our skills, we have to learn to dialogue with decision makers.

Why is working on climate change issues especially important for indigenous youth?

Climate change has had negative effects on indigenous territories where most of the biodiversity and genetic resources in indigenous territory are conserved. Even though indigenous peoples have maintained this harmonious relationship with the environment, biodiversity, and the territory, they are nevertheless feeling the impact of climate change. In view of the challenges of climate change, it is very important to work with the indigenous peoples who are able to provide advice on how to address this situation.

This is precisely the objective of the alliance established by the World Bank and FILAC with indigenous and academic organizations from the Latin American and Caribbean region and Spain: to strengthen the voice of young indigenous people in decision-making on climate change.

Angel points to three elements that must be incorporated in training programs for indigenous youth, emphasizing that “it is not simply a matter of regarding indigenous youth and peoples as empty vessels to be filled with knowledge, it is important to listen to what they have to say."

- Provide tools that can be used by indigenous youth within the global context in which society lives today.

- Combine the traditional knowledge and wisdom of indigenous peoples with Western scientific knowledge.

- Follow up with indigenous youth leaders who have already been trained to identify what they can do to return what they have learned to their community, and what impact they might have at a regional or international level. This would prevent a brain drain.