Don Armando Calderón is a 78-year-old peasant farmer with a lifetime dedication to working the land. Thanks to his hard work he managed to bring up his seven children in the Honduras district of Topaipí, a coffee town on the eastern cordillera of the Colombian Andes which has been the victim not only of the country’s historical violence but also disasters caused by climate change.

In October 2022, a landslide following heavy rains destroyed Don Armando's house and belongings, but he still has no intention of abandoning his property located on the slopes of the district. Just like Don Armando, more than 223,000 families in Colombia have lost their homes as a result of the torrential rains which battered Colombia in 2021 and 2022.

Topaipí currently is at high risk of remaining isolated from the Department’s main economic and commercial arteries, and as a result is likely to suffer even greater levels of poverty and food insecurity than at present.

The emergency in figures

Up to December 2022, the National Unity for Disaster Risk Management (UNGRD) reported 3,984 emergency events caused by heavy rains throughout the country. All 32 departments and 800 municipalities were affected, with 546,215 people suffering damage to their homes, etc, 226 people killed, 243 injured and 49 missing. In addition, the rains destroyed 3,775 homes, damaged around 3,000 roads, and seriously affected 457 education facilities, 471 aqueducts and 68 health clinics.

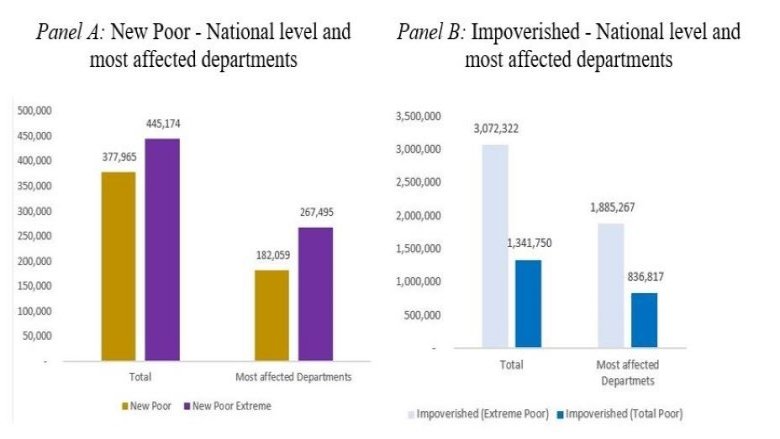

A study by the World Bank seeks to understand how different shocks, especially climate-related shocks, have impacted family wellbeing and health, as well as levels of poverty and income inequality. The study shows that events similar to the ‘Winter Wave’, which hit Colombia in 2010-2011, could lead to some 445,000 people falling into extreme poverty. Such extreme events could also affect the 3 million people already on the poverty line.

This kind of shock would affect people in rural areas more severely. Such areas already have fairly high levels of poverty, and less risk management capacity and ability to adapt to climate change risks (such as Topaipí). In the longer term, extreme weather events will further increase the persistent and already high levels of levels of inequality.

The ‘New Poor’ and people made poorer (impoverished) by climate-related shocks

Source : Own estimates, based on information from DANE- GEIH -2019

Strengthening the social protection system to address shocks

Responding to these shocks quickly and effectively helps mitigate the impacts on poor and vulnerable households – such as the loss of family income or access to education and health – as well as helping to prevent future shocks that could impact generations of people over the coming years. Achieving resilient social protection requires flexible policies, interventions and programs and the ability to respond quickly to shocks. In other words, a social protection system capable of adapting to circumstances.

The Stress Test Tool developed by the World Bank, and applied as a diagnostic instrument in at least ten countries globally, provides documentary evidence of how Colombia has achieved major progress in adapting its social programs and mechanisms for delivering assistance to the population when shocks occur (as seen for example during the COVID-19 pandemic). The diagnosis also reveals how Colombia has succeeded in strengthening and expanding its social register to identify poor and vulnerable populations and improve the focus of its social programs.

Resilient social protection system in Colombia

There are six short-term ways to improve response to shocks:

1. Adapt the design of the regular social assistance programs to include a temporary crisis framework or window, with funding that can be expanded at times of emergency.

2. Improve appropriate emergency early-warning systems for communities and municipalities, and use a multi-risk approach to monitoring the main disaster threats.

3. Strengthen coordination between disaster risk management institutions and social protection programs, including those responsible for social and beneficiary records, to ensure that disaster responses are more focused, timely and adequate.

4. Bolster coordination between policies relevant to disaster risk management, infrastructure, housing, health and education, in an effort to reduce the impact of damage caused by floods and landslides.

5. Incorporate aspects of risk management and climate change into development planning processes, policy decisions and local interventions.

6. Ensure interoperability between social registers, loss and damage databases, early warning systems and disaster risk assessments in order to mitigate potential damage to property and livelihoods, and determine more accurately who the likely recipients of assistance are, and the type of interventions required to help the most vulnerable population sectors.

Such policies, initiatives and actions which can help build the resilience of poor and vulnerable families like Don Armando’s to face climate shocks, will help countries like Colombia to work towards poverty and inequality reduction in a sustainable manner.

We thank Luz Stella Rodriguez, Juan Manuel Monroy Barragan, Carlos Eduardo Vargas Manrique and Maria Eugenia Davalos for their work in the production of this story.