Like many small island states already struggling with rising sea levels and violent storms, the Maldives is responding to climate change with bold plans centered around lowered carbon emissions and renewable energies.

Projected to lose 80 percent of its land over the next few decades, the country has some 50,000 residents living two meters above sea level on the artificially reclaimed island of Hulhumalé, where houses topped with solar panels generate an estimated 1.5 MW of power into a local grid.

“For us, addressing the issues of climate on both the mitigation and adaption side is critical for our survival,” says Aminath Shauna, the Maldives' Minister of Environment, Climate Change and Technology. “As a country that’s extremely vulnerable to climate impacts, taking the leadership in reducing our own emissions is also an important message to the world.”

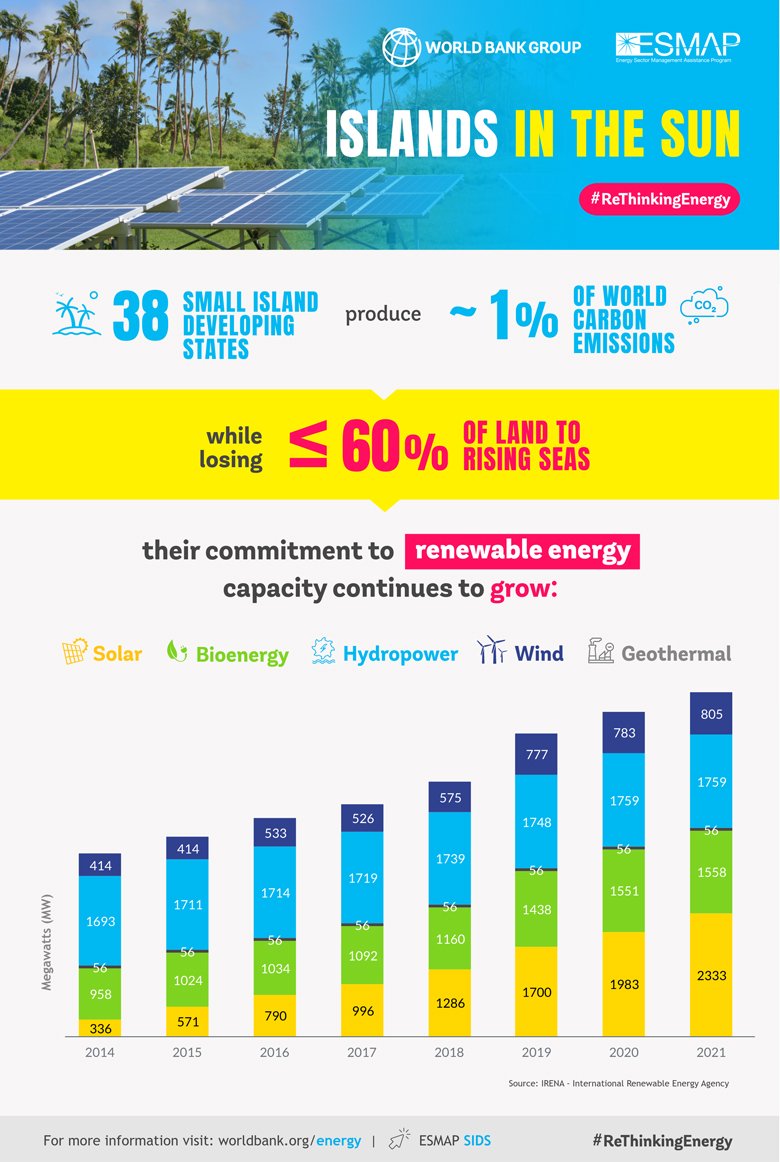

The United Nations recognizes that 38 small island developing states (SIDS), with an aggregate population of 65 million people, are facing distinct challenges, including loss of land to rising seas, high costs of imported goods, and increasingly violent hurricanes and cyclones. Many of these island nations like the Maldives are small, spread over vast areas of ocean, sparsely populated, and isolated.

It is both ironic and inspiring that these same small, vulnerable countries – among the first to bear the brunt of climate change while contributing less than 1% of global carbon emissions – are prepared to lead the way in the energy transition by harnessing sunshine, sea breezes, and water to create low-cost renewable energy.

Singapore is building a self-contained power grid on Semakau Island that uses Green Hydrogen to convert solar and wind energy into stored fuel that can generate electricity when needed, while the small nation of Cabo Verde off the coast of Africa is embarking on an extensive multi-faceted strategy to mobilize private and public capital for energy sector investments. In Jamaica, legislation to promote renewable energy has encouraged private consumers to install solar panel systems and integrate them with the national grid.

"Solar has cut my business expenses by 35 percent, allowing me to expand operations," says third-generation chicken farmer Shelly-Ann Dinnall, who installed solar panels on three massive coops seven years ago. "The primary motivation to go solar was cost savings, but I am pleased to know that I am doing my part to alleviate climate change considering its impact on islands such as Jamaica."

Renewable energies make sense for SIDS, many of which are archipelagos with populations spread across multiple islands. Fossil fuels must be shipped to small power plants and generators at a significant cost, representing up to 20 percent of the gross domestic product of some small nations. Shipping costs also drive up the price of electricity. In the Maldives, comprised of 1,192 islands stretching 510 miles across the Indian Ocean, reliance on imported diesel has resulted in some of the highest cost energy generation in South Asia at 30 to 40 cents per kilo-Watt hour (kWh) compared to 5-7 cents per kilowatt hour (kWh) in other neighboring South Asian countries.

However, despite their push toward renewables, most SIDS are still compelled to pay a premium for fossil fuels to keep existing generators and power plants operational. With their economies negatively impacted by a downturn in tourism during the global pandemic, they find it difficult to attract investment to build infrastructure.