By 2021, over 84 million people had been displaced worldwide, with 85 percent of refugees and Venezuelan migrants hosted in the Global South. Migrants fleeing their home countries often face nearly unimaginable circumstances, from violence to dispossession, disease, and poverty. In their new host countries, migrants may arrive in poor health and can lag behind native-born citizens in access to basic services, housing quality, and educational attainment even after years of living in these countries.

While many studies have investigated the question of what impact forced migrants have on host countries, far fewer have examined how host countries can most effectively support forced migrants in integrating into their societies—including by empowering migrants through access to formal labor markets.

“Most of the research on forced displacement in the past ten years has been focused on its impact on host communities. This research has looked at how native-born citizens are affected via education systems, health systems, and labor markets, or how their voting behavior might be affected,” said Sandra Rozo, a Research Economist at the World Bank. At a recent Policy Research Talk, Rozo reported on new research on Colombia that helps shift the focus onto the lives of the migrants.

With over 1.7 million Venezuelans, Colombia ranked second in the world in terms of total number of forced migrants as of 2021. In just six years, more than five million people have fled the humanitarian crisis in Venezuela and relocated to other countries, making Venezuelans the second largest internationally displaced population after Syrians.

In 2018, the Colombian government sought to count the number of Venezuelan migrants with an irregular status—that is, lacking authorization from the government to be in the country. To do this, the government opened the Registro Administrativo de Migrantes Venezolanos (RAMV) in April 2018. The program was not intended to regularize migrants, and registrants were not guaranteed anything in return for participating. Well over 400,000 people from more than 250,000 households registered as part of RAMV.

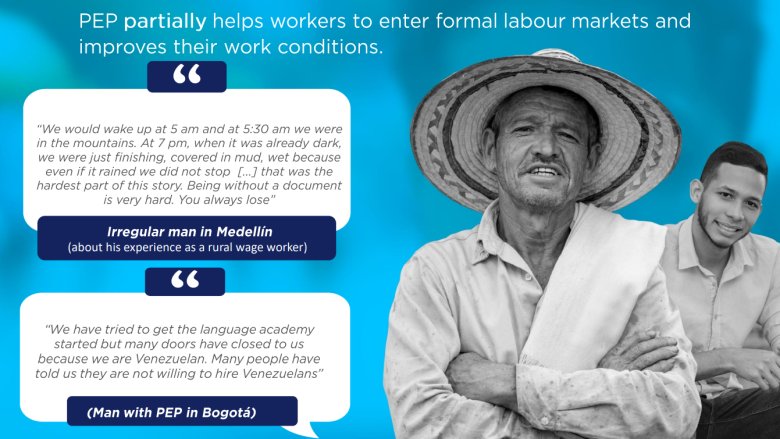

Following completion of the census, the government of Colombia announced a program called Permiso Especial de Permanencia (PEP), which offered amnesty on generous terms, including legal migratory status, a work permit, and access to government services (Figure 1). The program ran from August to December 2018, and approximately 60 percent of those qualified under the RAMV census signed up for PEP.

Figure 1. The PEP visa offered a generous amnesty to Venezuelan migrants, with registrants able to access safety net programs, banking services, and jobs in Colombia.

With all the data available from PEP, Rozo and her co-authors set out to understand various dimensions of migrant well-being including income and consumption, health (including physical and mental), access to state services, and integration into Colombian society. The team of researchers created a phone survey to collect representative data on the experiences of both those who were eligible and ineligible for the RAMV. Prior to initiating the phone survey, the researchers also conducted focus groups to help identify how to overcome mistrust and other social barriers that might limit migrants’ participation in the survey.

Given the generosity of the PEP program, the researchers expected positive results. However, they were surprised at just how much of an impact the program had. The immediate impacts included a 40 percentage point increase in access to state services, a 64 percentage point increase in access to financial services, and a 10 percentage point increase in labor formalization. Perhaps more importantly, those who received amnesty saw their incomes increase by over 30 percent and their consumption increase by 60 percent, as well as improvements in measures of their physical and mental health.1 These large benefits for migrants also accrued alongside minimal impacts on labor markets for Colombians.

During the course of her presentation, Rozo highlighted three key lessons for policymakers dealing with migrant crises. First, programs seeking to aid migrants and refugees benefit from using local language and signaling trust to the refugee population. Rozo and her co-authors were able to increase survey response rates by 15-20 percent when the language used was modified to Venezuelans’ day-to-day language. For surveys conducted over the phone, establishing trust with a vulnerable population is especially crucial. Local migrant organizations also played an important role in helping bridge the gap between refugees and researchers.

Second, many migrants who were qualified but did not register for RAMV or the PEP program lacked basic information about these initiatives. For example, among those who did not register for the RAMV but were qualified, approximately half stated that they did not know about the program. Many respondents also said that they did not apply for PEP because they did not have a passport, even though this was not a requirement of the program.

Finally, the PEP program was able to improve several measures of well-being among migrants by focusing on empowering and integrating them rather than just providing financial assistance. Although not a perfect comparator, studies of the impact of cash transfers for refugees suggest that PEP had more than twice the impact on consumption as cash transfer programs.

In addition to these material benefits, Rozo also stressed the broader benefits of helping migrants integrate more deeply into their new homes. “The PEP program improved how forced migrants feel in Colombian society. This is important because many of these migrants may never leave, and how they feel will determine how they choose to invest in the country,” concluded Rozo.

Figure 2: Community integration testimony from a forced migrant woman who was granted amnesty under the PEP program