With its audacity to legally guarantee each rural household 100 days of work per year through village Panchayats, India’s Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) has remained one of the world’s most complex and ambitious programs to implement. At the time of its launch, MGNREGS changed the very face of social protection in India. The program’s implementation architecture was an important innovation globally as well - with its focus on leveraging rights, technology tools, community-based accountability mechanisms and village Panchayats to respond to citizen demand for employment at scale.

What can the experience with MGNREGS tell us about the capability of the Indian state to implement large scale demand-driven programs? Three lessons are important.

First, despite the program’s ups and downs, its implementation continues to function at globally unparalleled levels. More than a decade into its existence, the reach of Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) remains impressive with nearly 51 million beneficiary households in 2017 generating 2342 million person-days of employment, and expenditures at 0.3% of GDP. Analysis of administrative data since MGNREGS’s inception shows that program participation has picked up after a phase of contraction in 2013 and 2014.

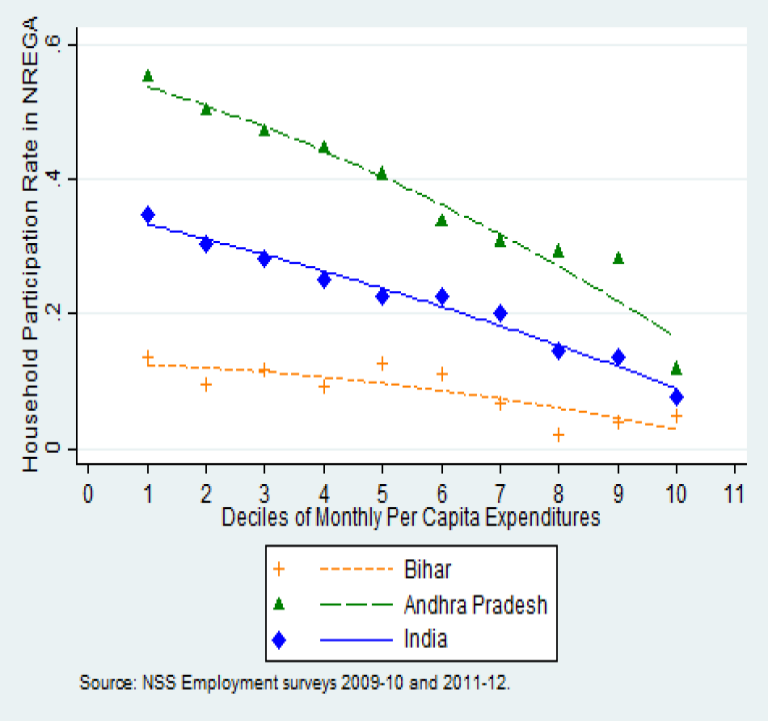

Second, local administrators and civil society have been able to leverage the program’s rights-based design to ensure pro-poor targeting. MGNREGS was one of the first national programs to delink program participation from any poverty criteria as it did not use the Below Poverty Line method of targeting. This ‘self-targeting’ design of MGNREGS appears effective in ensuring coverage of vulnerable populations and the poor. Most studies show that participation in the scheme favors poor households, and helps alleviate poverty and distress during crises. At relatively high consumption levels for all households, participation drops off sharply. The program also implemented quotas for women to prioritize female participation. In 2017, 53.5% of those provided employment through the program were women while 39.1% belonged to Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST).

Third, despite recent improvements, many states struggle to pay beneficiaries on time. In October 2017, the Supreme Court of India expressed concerns on the delays in MGNREGS wage payments. Most states have struggled in identifying an effective and speedy payment transfer mechanism for MGNREGS wage payments to beneficiaries. Major complaints revealed through household surveys and social audits data include non-issuance of dated receipts, non-payment of unemployment allowance, incomplete payment of wages, and especially, delayed payments.

At the same time, the program demonstrates the growing ability of the state to use information technology to tackle fund flow problems, with encouraging results. State and central governments have recognized the challenge of delivering timely wage payments and made concerted attempts to improve the speed and transparency of the benefit transfer process. State funds were established in 2011 to minimize the delays caused by the gap between state government requests for funds and central releases. In 2006, most of the muster rolls used to calculate wages were maintained in hard copy. By 2011, muster rolls were digitized for public review and 90% of program expenditure information was accessible on the MGNREGS MIS portals. Studies in Bihar and Andhra Pradesh highlight how re-engineering fund-flows through use of technology can reduce corruption and improve wage payment processes. Recent use of biometrically authenticated payments for wages also highlight the challenges imposed by technology, as activists and academics find exclusion and delays due to authentication failures. Ironing out technical glitches and improving infrastructure of payment systems is essential to ensure that intended benefits of the program are not undermined.

Theory and evidence suggest that public works can yield stronger welfare impacts than basic income transfers provided citizen demand for works is honored with supply of employment, and assets so generated are of high value. But, neither of these requirements can be achieved without a strong and capable Panchayat machinery. While the policy framework for ensuring flexibility in creating durable and locally valuable assets is in place, credible implementation requires investing in the ability of Gram Panchayats to define and plan their local shelf of works.

In fact, the inability of Panchayats to honor and respond to citizen demands stymies the program’s poverty impacts. MGNREGS performance has been weak in poorer states, where it is needed the most. High levels of unmet demand for work under the scheme constrain poverty impacts. According to recent administrative data for 2017, the nine poorest states – with poverty rates higher than the national poverty rate --account for only 32% of the total employment generated. Recent evaluations in Bihar and Rajasthan show that weak local implementation dampens the program’s poverty effects despite effective targeting. As the chart below shows, a household in the poorest decile is four times less likely to participate in NREGS in Bihar than in Andhra Pradesh (13% against 55%). Strikingly, participation in NREGS in the poorest decile in Bihar is about the same as program participation in the richest decile in Andhra Pradesh (12%).