The author, Bertha F. Wilson, is an archivist at the World Bank Group Archives in Washington, DC where she has worked for 24 years. As a member of the Archives’ Access to Information team, she works with external researchers to facilitate access to the Bank’s historical records. In this article, her fourth contribution in a series that celebrates Black History Month, Bertha focuses on the first U.S. African American Executive Director, Colbert I. King, and the impact he had on the Bank during his tenure.

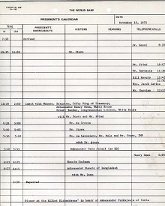

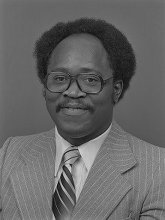

As an archivist at the World Bank Group Archives, I encounter many historic figures in the pages of the archives. One of these is Mr. Colbert (Colby) I. King. Mr. King was the first African American to represent the United States as a World Bank Executive Director (ED) after he was nominated by President Jimmy Carter in 1979. Prior to his appointment, he served as a deputy assistant secretary of the U.S. Treasury and had occasion to visit with the World Bank President, Robert McNamara, at a lunch on November 15 the year before his appointment [1].

Mr. King was born in Washington, DC in 1939 and grew up in Foggy Bottom which is, incidentally, the location of the World Bank Group Headquarters. Mr. King’s elementary school, the historic African American Thaddeus Stevens Elementary School, constructed in 1868, was the oldest public school in D.C. in operation until it was shuttered in 2008 [2]. I was excited to learn that Mr. King and I both attended Francis Junior High School and Howard University. He graduated from Howard University in 1961 with a degree in government and I was a Howard student during his tenure as Executive Director from 1979 to 1981. Also, my mother and Mr. King graduated from the same high school, Paul Laurence Dunbar, and my great-niece is currently a Dunbar honor roll student.

Mr. King officially took the role of U.S. ED on December 21, 1979. As U.S. ED, he was a very prominent figure in Board discussions; this was particularly the case in the early months of 1981. At this time, the world of development economics was in flux as it navigated an ongoing worldwide recession and the new Reagan administration that had just taken office in the United States. The World Bank Group was at a transitional point with long-time president Robert McNamara about to retire, a new focus on structural adjustment financing emerging, and, significantly, questions intensifying about the effectiveness of the International Development Association (IDA). During this period, Mr. King served as a key voice both in how he represented his country's interests and in consensus building within the Board of Executive Directors. This was especially true during the days surrounding the January 27 and 28 Board meetings of the World Bank Executive Directors.

Mr. King’s role at the Board Meetings in early 1981 was impactful because he set the tone and framed the discussions on the role of the World Bank in the 1980s. Many of the topics he discussed were included in the summary of issues and questions raised by the Executive Directors [3]. Mr. King was a key participant in discussions concerning the IBRD/IDA Lending levels [5], financing IDA’s sixth replenishment (IDA VI), and the Burkina Faso (then Upper Volta) Second Bougouriba Agricultural Development Project [4].

“Assuming that the level of external assistance remained relatively the same, if I returned to that very spot ten years later, would conditions be any different. And after a long pause, he said no, and what his 'no' meant to me was that the needs of Upper Volta -- and I believe we could really apply this to the Upper Voltas of the world are so great and are going unmet in such a large measure that the levels of assistance that we were giving then and that we're giving now, in a sense, only maintains some countries above the level of subsistence.”

In these Board meetings in January 1981, Mr. King addressed the concerns that several Executive Directors had about the status of U.S. participation in financing IDA VI, which precipitated impassioned queries by Mr. King’s Board colleagues. To assuage the fears of the EDs that IDA may be under threat, Mr. King took extra steps to discuss U.S. assistance to IDA VI with his peers in a special session outside the normal Board meetings.

Bank senior management discussions regarding IDA VI took place a week later at the February 2, 1981, President's Council (PC) meeting where McNamara informed his team that the press statements about the threat to IDA VI financing from the US were true. McNamara also mentioned that he and Mr. King were working hard to address the problem with other EDs and senior US officials. The archival records give clues that the next three weeks in February were tense, and that Mr. King was keeping McNamara informed. By February 23, at another President’s Council meeting, McNamara was able to inform his team that the efforts of Mr. King and others had been successful: that the US Administration intended to fulfill its commitments to the Bank and IDA.

In his farewell remarks to the Board in the spring of 1981 (captured in the April 1981 issue of the Bank’s internal newsletter, Bank Notes), Mr. King recounts his youth growing up in a segregated Washington, DC where it was against the law for him to attend a certain school, sit at a drug store lunch counter, or enter a movie theater because he is Black. My mother shared similar experiences in DC and vowed never to shop at certain stores even after integration because we were not welcome. In 21st century Washington, DC, I have experienced this unwelcomeness in certain spaces but, like Mr. King, I forge ahead and claim my place.

***

A list of publications and a selection of other related resources, some of which have been used to write this article, is available here. Footnotes are indicated by the corresponding number preceding the citation information.