Globally, most workers are in the informal sector and do not contribute to pension systems. At the same time, the proportion of elderly people is increasing worldwide, not just in historically wealthy countries but also many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). If the world hopes to achieve universal social protection, governments will need to devise new policies that can reconcile these two facts.

At a recent Policy Research Talk, World Bank Research Economist Clément Joubert shared new research on pensions and pension policy design to help address this challenge, focusing in particular on countries where informality is prevalent. “Most workers worldwide do not contribute to pensions,” said Joubert. “Even in cases where individuals contribute to pension plans, very few individuals contribute consistently over their lifetime.”

Joubert pointed to several factors that push workers out of pension coverage and into informality and thus lead to underfunded or inadequate pension systems. Common issues include a bias toward present over future consumption—as anyone who has overspent their budget well knows—and liquidity constraints when a household’s income does not allow for any saving beyond meeting basic needs. Women’s pensions are particularly at risk as women are more likely to either cycle into the informal sector or leave the labor market altogether.

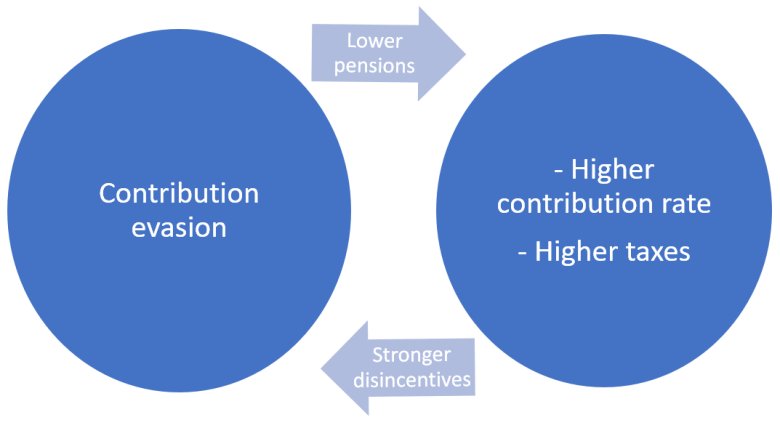

Workers using informality to escape pension contributions can create a vicious circle for pension funding (Figure 1). The lower contributions generate pressure to increase either pension contribution rates or taxes, leading to more significant incentives to evade contribution and then to greater pressure to increase contributions, which can become a vicious circle. The resulting levels of evasion can lead to unsustainable pension systems and the need for periodic reforms.

Figure 1: The Vicious Circle of Contribution Evasion

To better understand what can make a pension system more sustainable, Joubert applied an analytical framework to data from Chile and Pakistan—two countries with significant but varying degrees of informality. The framework places the most important factors in a worker’s decision about working in the formal or informal sector into three categories: (1) wages; (2) non-wage factors (e.g., greater flexibility in one sector over another); and (3) longer-term considerations such as the accumulation of skills, pension savings, and eligibility for government transfers.

With this framework in mind, Joubert first turned to the case of Chile to ask the question: “Do pension rules generate informality?” Drawing on nearly three decades of data since Chile reformed its pension system in 1981, Joubert found that increasing pension contribution rates can cause workers to shift out of the formal sector and into informality. Increasing the contribution rate by ten percentage points, causes informality to increase among men by over eight percentage points and by over five percentage points among women. The effects are largest among young workers and those already only intermittently contributing to the system.

Joubert examined another reason why pension systems can encourage informality. In the past, Chile’s pension system provided a guaranteed minimum pension for retired workers. For workers who are likely to only receive a minimum pension, any additional contributions to the pension system would bring them no additional benefit—equivalent to a 100 percent tax. In principle, a tapered minimum pension could reduce this disincentive to make additional contributions, but Joubert found this had little effect on rates of informality except among those who were already close to retirement age.

An example from Pakistan further illustrates how problematic informality can be. Nearly 90 percent of the Pakistani workforce is in the informal sector, creating a massive challenge in ensuring the well-being of the elderly. In cases like Pakistan, where informality is widespread, many of those who work in the informal sector are not from poor households, which means they are covered neither by social safety nets for the poor nor by formal pension systems.

In such a context, Joubert wanted to know whether a voluntary pension scheme targeted to the informal sector might meet the needs of an aging population—particularly the non-poor households in the informal sector. Drawing on data from eight surveys conducted over 18 years, Joubert found that Pakistani households are already accumulating significant wealth on their own. On average, a household accumulates wealth equivalent to 4.2 years of household consumption as the household head ages from 25 to 65. Further, most of this extra wealth is in the form of housing, which is difficult to draw from in moments of need and can therefore be considered a long-term savings instrument. The finding suggests that a voluntary pension scheme might provide households with an alternative and possibly more secure instrument to prepare for old age.

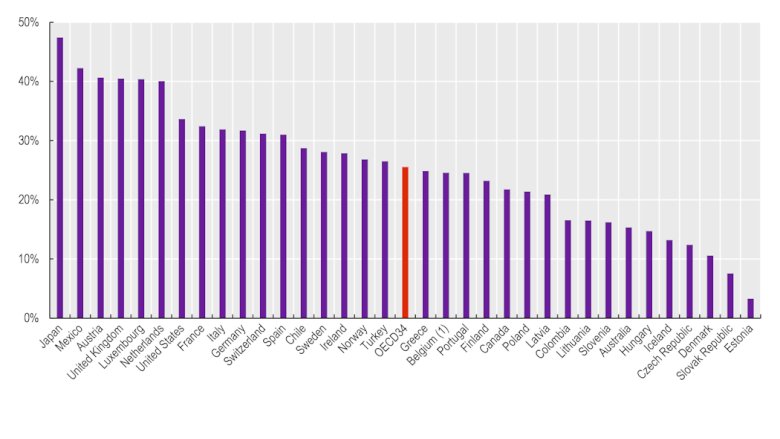

Turning to the other side of the ledger, Joubert also examined the uneven distribution of pension system benefits between men and women. Gender pension gaps are significant in countries around the world (Figure 2). The reasons for this are multiple, including poorer opportunities for women in the labor market, a greater likelihood of women exiting the labor market, and gendered rules in pension systems, such as different retirement ages for men relative to women.

Figure 2: Gender Pension Gaps by Country

Returning to the case of Chile, Joubert examined two different policy options that might help ameliorate the gender pension gap between men and women. The first option—increasing the minimum pension benefit—is the one that Chile enacted in 2008. The policy entailed increasing the level of the benefit, removing a contribution requirement, and easing the means-test requirement. The result was dramatic, nearly halving the gap from 44 to 23 percent. A second policy option—to match retirement ages between women and men—was projected to have almost as dramatic effects on the gender pension gap but was not implemented by the Chilean government. While this second option would have resulted in higher pension benefits for women, it also would have come at the cost of eliminating the option for women to retire earlier.

Joubert highlighted crucial unanswered questions, knowledge gaps, and policy implications. “Since the 1990s, economics research has made great progress towards understanding the economic lives of the poor,” said Joubert. However, more research is needed on non-poor informal workers, often not covered by social safety nets. Truly durable solutions to extreme poverty must provide the kind of universal social protection that not only lifts people out of extreme poverty but also protects those who face the threat of extreme poverty at vulnerable moments in life.