“They treated us very well; they didn’t ask for any bribes. Their behavior was very good,” reads a text message from a resident of Toba Tek Singh, a district in Punjab, Pakistan’s largest province. The sender had visited a government-run emergency room the day before and was responding to an automated message sent by the government of Punjab to track service delivery quality.

With technical assistance of the World Bank and support from the Department for International Development’s (DFID) Sub-National Governance program, the provincial government, responsible for over 100 million of Pakistan’s 180 million people, has been using mobile phones to tackle some of the most prevalent grievances citizens have against the government – poor service delivery and corruption.

Direct feedback from citizens is gathered thanks to the Citizens Feedback Model. Shortly after using a government service, the user receives a phone call followed by an SMS seeking his/her feedback.“Dear citizen, did you experience any corruption when obtaining your driving license yesterday in Lahore?,” reads a typical text message. Responses from users are logged into a central database, and the data then analyzed and mapped. Call centers have also been trained to contact those who do not respond or are unable to read the text due to illiteracy. More than three million users of public services have so far been contacted since the summer of 2012, with both positive and negative feedback. “Sir, we went to the hospital yesterday. They asked for 1500 rupees [in bribes]. We didn’t have the money so we left,” reads one of the reports about a hospital in Lahore, the provincial capital. The feedback is actively monitored by the office the Chief Secretary – the top civil servant in the province – to manage the performance of officials.

Tackling absenteeism

These applications are expanding to improve other services as well. In Pakistan, as in many other developing countries, absenteeism is a serious problem for improving quality of service delivery - the rate of absenteeism for doctors, for example, is close to 50%. Anecdotal evidence suggests that absenteeism is even higher for field workers, who are more difficult to monitor than those posted to stationary facilities. Visual analysis of activities performed by agricultural extension workers suggests that farmers away from the roads receive far fewer visits.

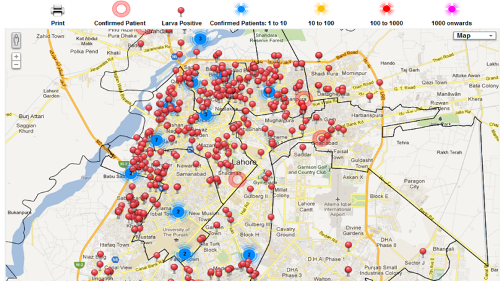

The Monitoring the Monitors Program, seeded by a World Bank Innovation fund grant and scaled up by the International Growth Centre, uses smartphones to tackle this problem. Health inspectors are given a smartphone and log the results of their visits to health facilities, including a photo to prove that it happened at the said time, allowing for both live time and spatial monitoring, completing the accountability loop. The Punjab Information Technology Board (PITB), the information technology arm of the government of the Punjab deployed smart phones successfully last year in fighting the dengue epidemic that hit Lahore in the summer. City workers were given smartphones to upload and geotag pictures of their anti-dengue tasks which allowed both a visualization of where larvae where, as well as ensure they did their jobs. The visualizations were also publically available. Compared to 2011, when over 21,000 people contracted the virus, 2012 saw just 255 cases in the city of 10 million people.